No place like home: how the go-home factor is making it increasingly difficult for AFL clubs to retain and recruit talent

The ties that bind players to their home states remain a powerful force with the potential to undermine the AFL’s socialist ideals, writes DANIEL CHERNY.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

This article is free to read for a limited time. For full access to Australia’s highest rated sports journalism app, trial CODE Sports now at a low introductory price. Click here.

If the “go-home factor” has a face, it is the emotionless gaze of Tanner Bruhn as he hugged loved ones after having his name read out with pick 12 of the 2020 draft.

The Geelong Falcons midfielder had just been drafted by Greater Western Sydney, and his expression became something of a meme on draft night. This was the disposition of someone not overly thrilled with the idea of leaving home for Homebush.

In the days afterwards, Bruhn explained his reaction as typical of his reserved nature, insisting that he was happy to be joining the Giants.

But 18 months later, Bruhn, despite playing regular senior footy this year, is yet to re-sign beyond his initial pro forma two-year draftee contract. There is no indication that he will do so either, and the widespread expectation amongst player movement sources is that Bruhn is likely to be playing at a Victorian club in 2023.

The point here though is not to single out Bruhn. He is just one example; his draft night persona was a neat representation of a phenomenon that continues to play a crucial role in the AFL player recruitment ecosystem.

The competition went national well over three decades ago, and a draft has been in place that whole time, yet the ties that bind players to their home states remain a powerful force with the potential to undermine the league’s socialist ideals.

To investigate the extent of the issue, Code Sports canvassed the views of a host of club officials and player agents, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The AFL models its draft and salary cap equalisation measures based on those used in the NFL and NBA. But as one senior football department administrator noted, there is a considerable cultural difference between Australia and the US in the sense that whereas Americans tend to travel interstate for college, it is more common in Australia for people in their late teens and early 20s to remain in their home towns and cities.

If all your friends were going off to different cities after high school there would be considerably less incentive to stay home. But when your networks largely remain in the same place, it is little wonder that in an ideal world you would want to stay there.

While the AFL is a national competition (this is not an invitation to debate the Tasmania issue!) the fact that more than half the league’s clubs are based in Victoria further complicates the situation. In recent years Victoria has had roughly proportional representation in terms of players of origin relative to clubs. South Australia and Western Australia, both with two clubs, have been slightly overrepresented. There have been small clusters of players from Tasmania, the NT, ACT and overseas.

But the two states that are generally underrepresented in terms of players to clubs are NSW and Queensland, which should of course be no surprise given they are not traditional Australian rules football states.

This ultimately makes the NSW and Queensland clubs particularly vulnerable when it comes to the “go-home factor” given they have a smaller pool of players to be able to lure on that basis. The Giants and Gold Coast have in particular been pillaged over their relatively brief histories, with both losing a stack of talented players back to Victoria. In part this has been by design.

Both clubs, but especially the Giants, were given a raft of draft concessions, meaning that their early lists were stacked with top-end draftees from interstate. Inevitably some were going to leave, allowing GWS to parlay those departing players into further early draft picks.

However, problematically for the Giants, they have not tended to get a full price return on their departing players. The club was highly aggrieved in late 2020 when Jye Caldwell and Jackson Hateley returned to their home states in moves to Essendon and Adelaide respectively. But while both had been drafted two years earlier in the first round, the Giants got only second-round selections in a swap with the Bombers for Caldwell, and got nothing for Hateley after the Crows used their leverage of holding pick No.1 in the 2020 pre-season draft to procure the South Australian midfielder.

It would be understandable if they feared a similar outcome should Bruhn decide to follow that path. Having lost Tom Lynch, Dion Prestia, Steven May and Jaeger O’Meara (who headed to Victoria instead of his native Western Australia) amongst others, the Suns have fortified their ranks in recent times to re-sign most of their early draftees. Clearly there is an environmental factor at play. Gold Coast is a considerably stabler and more attractive club at the moment, but whether these levels of retention are sustainable remains to be seen.

The Brisbane Lions to their credit righted a badly flailing ship on the back of an exodus at the end of 2013. Part of their resurgence has been a concerted strategy to recruit players from regional Victoria who have less of an incentive to head to Melbourne. Sydney has been the least hit of the four Northern market clubs. This can to an extent be attributed to the Swans’ success and culture, but they have also not had nearly as many early draft picks from interstate; the type of player that is usually in the go-home factor hitting zone.

Even so, Sydney were very disappointed to lose Jordan Dawson to the Crows last year, particularly aggrieved by what they perceived to be use of the pre-season draft as a bargaining chip.

One Victorian list boss admitted that he was glad not to have to deal with the issues experienced by the NSW and Queensland clubs. Another official who has worked at both a Victorian club and a Northern club noted the issue of retention never rated a mention in Melbourne, whereas it was a preoccupation in the expansion markets.

It would be incorrect, however, to think that this problem is purely the domain of the NSW and Queensland clubs. The Crows have been on both sides of the ledger - they lost Patrick Dangerfield to Geelong in 2015. The Cats have had it both ways too, with Tim Kelly moving back to WA to join West Coast at the end of 2019.

What is interesting with that example is that despite knowing that Kelly had family challenges which would make him a reasonably likely go-home candidate, Geelong took a punt on the mature-age midfielder, getting two excellent years from him and then reaping a trade bonanza when he eventually headed back to Perth.

This takes us to the intriguing question of whether clubs should draft players if they know they are flight risks. Draft rules dictate that once someone nominates they have to go anywhere, but that hasn’t stopped a handful of players in recent years from trying to manoeuvre their way to a local club. Bailey Smith (drafted to the Western Bulldogs in 2018) and Archie Perkins (drafted to Essendon in 2020) are probably the two highest profile examples. There have been several others though; Geelong star Tom Stewart has admitted he tried to massage a path to his local Cats, while there are already concerns from several non-Victorian clubs about one of this year’s likely early draftees.

Smith, who has been public about his mental health issues, told non-Victorian clubs that he feared he would not cope away from home. Perkins’ issues were less acute but he made headlines by going on SEN on draft day and declaring that he’d told interstate recruiters that he didn’t want to leave Victoria.

Perkins created a storm with his comments, but as noted in recent days by one player agent, clubs probe players for all sorts of personal information in the lead-up to the draft in a bid to better understand their potential recruits so they can hardly complain when a teenager is honest about their preferences.

One counter-view espoused by a recruiter is that it is hard for clubs to quantify the extent to which a player may struggle interstate. Clubs receive detailed physical examination summaries and psychometric testing results of players but don’t receive any mental health records.

Having done their due diligence, clubs undoubtedly end up ruling players out at the draft because they deem them unlikely to stay, leaving a bitter taste in the mouths of some recruiters. And agents have been known to use the go-home factor as a chip in negotiating contracts, so that even if a club does keep a player, they in effect pay a retention tax for doing so, a recipe for a bulging salary cap. Both the Giants and Suns have experienced this phenomenon.

For clubs that do end up rolling the dice on a player who appears destined to one day leave, one of the challenges that can pop up is how to deal with that player in the season in which it looks like he will depart, especially if the team isn’t in contention for the finals. There is an argument that the player should be left to rot in the reserves as he isn’t part of the club’s future, but that has to be countered against a potential hit to his currency come trade time. Loyalty is of course also a two-way street, as one agent pointed out. Clubs aren’t necessarily that accommodating with allowing players to return to their home states in-season.

One agent noted that clubs, and by extension the football media and public, should be cautious not to lump all players into the same category when it comes to the go-home factor. Each player has different circumstances. For the club therefore it is critical to understand the different hurdles in front of any given player to best allow them to stay and ultimately thrive.

Inevitably when collective bargaining negotiations are on the horizon, the topic of extending the initial contracts of draftees from two years to three as a retention mechanism arises. While the expansion clubs would reap benefits, it is unlikely the AFL Players’ Association would allow such a concession without a considerable carrot in return.

For now, however, it appears likely that the go-home factor isn’t going anywhere. Even mighty Melbourne, having won a premiership and appearing in likely contention for several more in the coming years, are at major risk of losing emerging star Luke Jackson back to his home state of Western Australia, with Fremantle his expected destination amongst trade sources.

If the go-home factor is working against you, hate the game, not the player.

Trending now

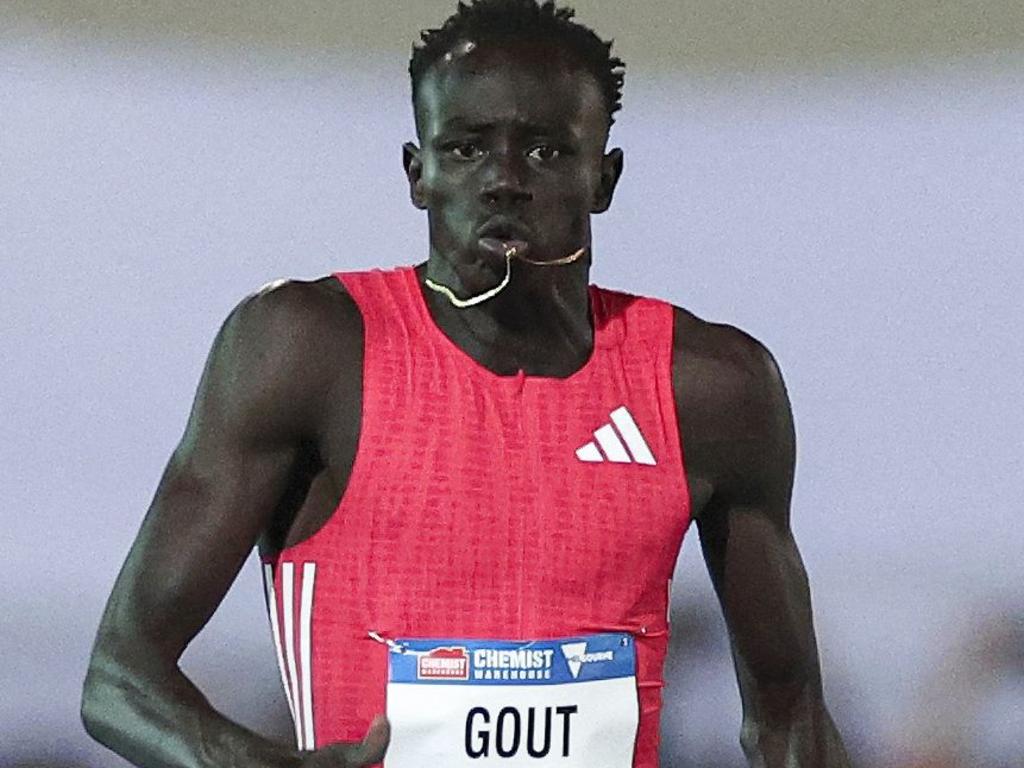

Gout Gout’s latest bid for history: What is on the line in Perth

Third boost down or hold trades? See what the experts are doing

SuperCoach: Another gun rookie, prices falling on big guns

Knights raid Dragons: Ex-Aussie schoolboy spotted in Newcastle