The pain you didn’t see as Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle chased Babe Ruth in 1961

Six decades after Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle duelled for Babe Ruth’s hallowed single-season home run record, the legacies of that 1961 season endure and its scars remain.

“Sixty! Count ’em, 60! Let some other son of a bitch match that!” — Babe Ruth

***

The crowds swell in the summer, when the sun accepts a starring role and baseball is most firmly entrenched in our identities. Tourists come from all over — from the Great Plains, from New York, from the major league city a three and a half-hour drive away (Minneapolis) — to visit the Midwest monument.

“Roger Maris still gets a lot of visitors,” said a part-time bookkeeper at Fargo’s Holy Cross Cemetery, whose North Dakota DNA and Maris-like aversion to publicity demands he request anonymity. “Nobody forgets Roger Maris.”

It was snowing, and the temperature barely broke zero, when Maris arrived at his final resting place on December 19, 1985. He had requested to return to his hometown, to be interred where the family of his wife — and high school sweetheart — had been buried.

Governor George Sinner ordered all flags to be lowered to half-staff. Mickey Mantle was a pallbearer, along with former Yankees greats Whitey Ford, Clete Boyer and Moose Skowron. Bobby Richardson delivered the eulogy. Funeral attendees received programs, featuring a picture of Maris in pinstripes, in the midst of his 61st home run swing of 1961.

He was forever 27. He was forever plagued by the brilliant legacy that would long outlive him.

“Roger electrified the baseball world and the nation in 1961, and it should have been, and deserved to be Roger’s finest moment,” Richardson said at the service. “… But he was misunderstood. He was a private man who wanted to go home after the game, be with his family. He didn’t take much to the acclaim and adulation of the hero.”

Fargo still celebrates its most famous son. The Roger Maris Museum is housed inside West Acres Mall. Along Roger Maris Drive sits Lindenwood Park, where a memorial of the two-time MVP sits at the entrance. A few miles north is the Roger Maris Cancer Center at Sanford Hospital. Another few miles northwest lies Maris.

Former Brooklyn Dodgers (NFL) fullback Stan Kostka is buried there, too. So is Ronald Norwood Davies, the judge who ordered the desegregation of schools in Little Rock, Arkansas. Beside Maris is former teammate Ken Hunt, who requested the plot next to his long-time friend.

The grounds’ main attraction warrants a small green sign, pointing from the edge of the pavement to Maris’ spot in the middle of the section. The surrounding stones are all some version of the same uneven rectangle, failing to differentiate McLaughlin from Stine from Quarve.

A large black diamond towers over its granite neighbours. It is simple and dignified. It is plain but powerful. It stands out without screaming out for attention. It is Maris.

At the base of the headstone, visitors place baseballs. Some leave a cap, a bat, a glove or 61 cents. Below the engraving of his name, Maris is pictured in the middle of his most legendary swing. Above the bat is “61.” Below the bat is “’61”. Farther down is an inscription: AGAINST ALL ODDS.

“It was against all odds for what he had to endure, and a lot of people think that’s why he’s in the grave, truthfully, because of the stress of what he had to go through in New York and the toll it took on his body,” Roger Maris Jr. told Post Sports+.

“For him to persevere and still do what he did, it’s amazing. He was 27 years-old. He grew up in Fargo, North Dakota. The more I look back at it and think about it, if you look at the greatest records in sports and think about what did that person have to do — the stress, what dad had to endure against the icon of baseball (Babe Ruth) and Mickey and New York and the press and the excruciating pressure — for him to pull it off is unbelievable.

“He would always say, it was the best and worst thing that ever happened to him.”

***

Hack Wilson hit 56 home runs in 1930. Jimmie Foxx hit 58 in 1932. Hank Greenberg blasted 58 in 1938. Ralph Kiner had 54 in 1949.

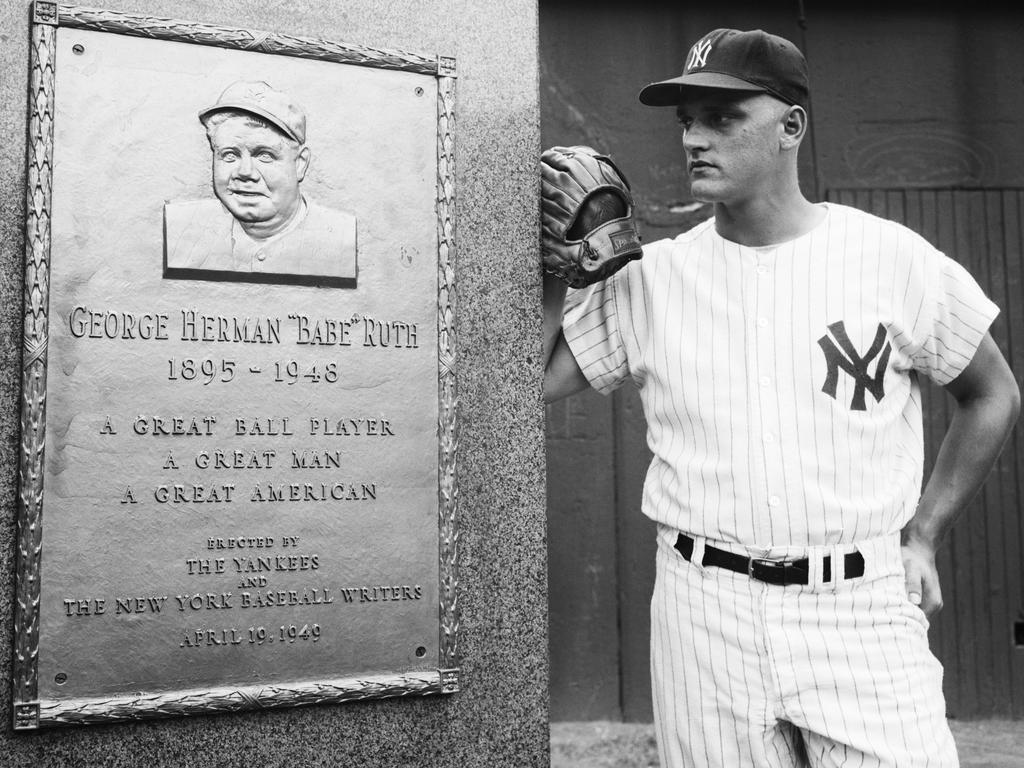

Unlike when Ruth arrived in New York and forever altered the sport by hitting more home runs than entire teams did, besting his record-setting 60 homers (1927) should have felt feasible by 1961. Yet, the prospect of breaking the 33-year-old record and surpassing the game’s greatest legend remained far-fetched.

“It looked like a record that was beyond breakable,” said Richardson, an eight-time All-Star and former World Series MVP. “It really did.”

No one came close the season — or decade — prior. Ernie Banks led the majors with 41 home runs in 1960. Mantle had 40. Maris had 39.

It had been an eternity — two years and counting — since the Bombers were champs. The wound from the stunning World Series loss to Bill Mazeroski and the Pirates was still raw. The Yankees opened the ’61 season at 17-15.

But Mantle never hid his numerous injuries better. He hit nine homers in his first 18 games. Maris, the reigning AL MVP — beating Mantle in the closest vote ever — didn’t hit his first homer until April 26. On May 16, Maris had three home runs. He was batting .208 and had been dropped to seventh in the line-up. The struggles made Maris concerned about his vision, prompting an eye examination at Lenox Hill Hospital. Owner Dan Topping and general manager Roy Hamey were worried Maris’ priorities weren’t straight.

“We’re not paying you to hit .300 or better,” Hamey said during a lunch sit-down. “We’re paying you to hit home runs.”

Maris soon went on one of the greatest power surges in history, crushing 24 home runs in 38 games. Hitting in the 3-hole, Maris — who wasn’t issued an intentional walk all season — enjoyed the protection of Mantle at clean-up, following a line-up switch manager Ralph Houk made early that season. Mantle, then 29, hit 11 homers in June. Maris hit 15, including eight in 10 games. Maris had 33 home runs at the All-Star break. Mantle had 29.

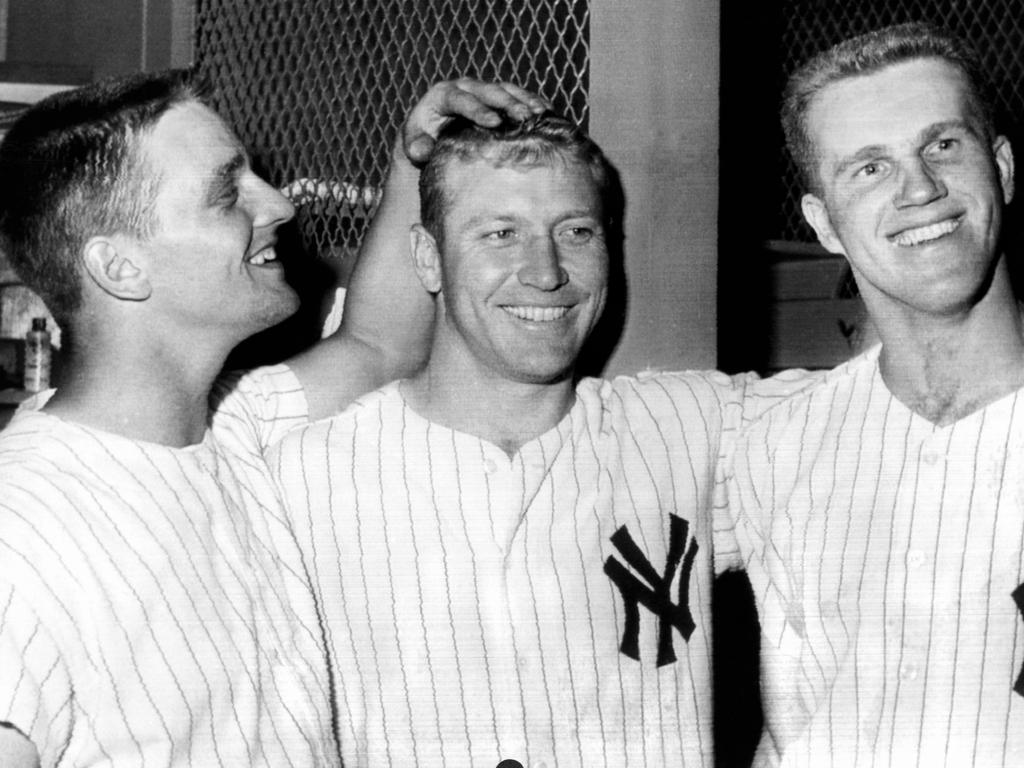

Rollie Sheldon has a photo on the wall of his Missouri home, commemorating his first victory on the mound as a rookie that season. Mantle is to his left. Maris is to his right.

“They both hit home runs in that game,” Sheldon said. “I was always in awe of those guys.”

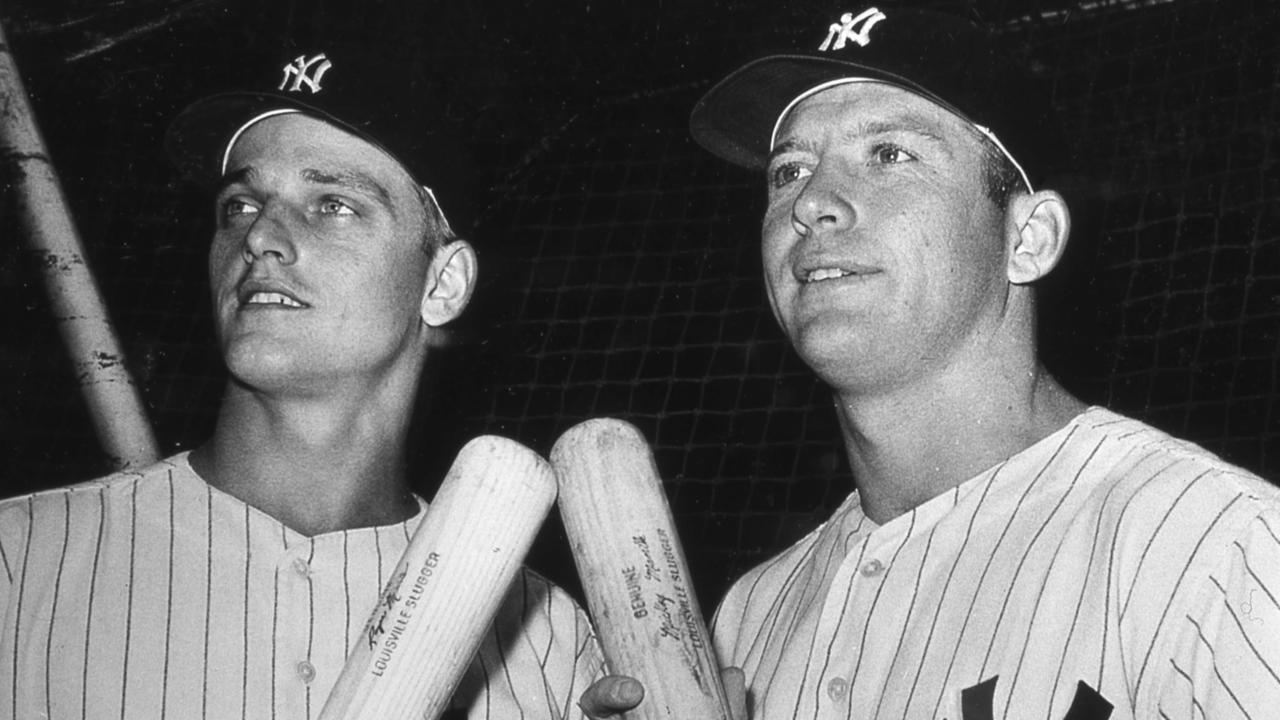

The M&M Boys were the biggest story in sports. They made endorsement deals. They graced magazine covers. They appeared in a pair of movies (“Safe at Home” and “That Touch of Mink”). They were a daily presence, alongside Ruth, in countless newspapers across the country, listing their respective home run totals on that date.

Few believed Maris could maintain the record-setting pace. Mantle — the once-prized prospect who began his career wearing No.6, following the footsteps of Ruth (3), Lou Gehrig (4) and Joe DiMaggio (5) — was the natural heir to the throne.

“Mickey was just overpowering,” said Orioles slugger Jim Gentile, who finished third in the majors with 46 home runs that season. “He was the greatest. Everyone was looked as under him. Everyone expected Mickey to do that every year. But Roger held his own. He had a beautiful swing. He was never off-balance.”

***

Merlyn Mantle and her four boys were back in Dallas. Pat Maris and her three kids were in suburban Kansas City.

Roger and Mickey were sharing a $251-per-month apartment in Queens beside the Van Wyck Expressway, along with veteran outfielder Bob Cerv. Mantle began the season in a suite at the Hotel St. Moritz on Central Park South, but he was persuaded to curb his legendary carousing and sample a simpler existence in the outer borough.

“It was a lot calmer,” said Mantle’s son, David. “He’d be sitting there watching Andy Griffith instead of going out to bars. He saved a lot of money.”

The two-bedroom apartment left an MVP (Maris) sleeping on the living room couch. Girls were prohibited. Baseball was rarely discussed. Commutes to The Bronx came in Maris’ Oldsmobile convertible.

“They got along great, even though Roger was more reserved and quiet and Mantle was free-swinging on and off the field, wanting to have a good time,” Sheldon said. “The rules were different that Bob Cerv set, that, ‘Hey, we’re in the middle of a pennant race and you’re doing good and we’re gonna settle in here and not go downtown and booze it up’. Cerv served a good purpose in that apartment.”

Maris and Mantle found humour from hurling music records from their balcony. They found amusement from reading newspaper reports of alleged fighting between the teammates and roommates, whose at-bats merited news bulletins.

“Those guys were really good friends, both Midwestern guys, just peas in a pod,” Maris Jr. said. “They hit it off great. They had a lot of fun together and they’d see each other [after retiring]. They were good buddies until my dad died.”

Reports of tension between the stars were untrue, but were understandable.

The previous season, Maris edged out Mantle for MVP honours despite the latter winning more first-place votes. Mantle made around $75,000 in 1961. Maris earned $32,500. Fans who long bemoaned Mantle for falling short of DiMaggio’s iconic standard began embracing their long-time centre fielder, rather than the right fielder who arrived one year prior in a trade from the Kansas City Athletics.

“[Mickey] said that was the first year they didn’t boo him because they were booing Roger,” David Mantle said. “He enjoyed that. He said, ‘No wonder I was doing good, I didn’t have any pressure on me’.”

Teammates weren’t much better at hiding their preference.

“Roger knew that we were all pulling for Mantle, that he should be the one to break Babe Ruth’s record,” Richardson said. “Because he had grown up as a Yankee and we had played with him all those years.”

***

What more could you want?

After nearly seven weeks riding shotgun, Mantle took the lead with his 36th homer on July 19. Maris evened the score in the first game of a July 25 double-header, Mantle went ahead in the next at-bat, then Maris finished the two-game set with another three bombs. Mantle jumped in front with three homers on August 6. One week later, each player — who each lost home runs in a July 17 rainout — hit his 45th home run.

Mantle never again led the race. Maris would cross the finish line alone.

Mantle hit his 53rd home run on September 10, then went nearly two weeks before hitting his final one of the season. During the stretch, he battled flu-like symptoms, prompting broadcaster Mel Allen to make an appointment for him with Dr. Max Jacobson on the team’s off day on September 25.

The secret service called him “Dr. Feel-good,” a shady physician who treated several celebrities, whose mysterious miracle shots were favoured by President John F. Kennedy. Mantle took one at-bat the day after his injection, then suffered an infection and was admitted into Lenox Hill Hospital with a hip abscess, ending his regular season. Mantle and Maris still hold the single-season record by teammates with 115 combined home runs.

“They had no jealousy, and dad was always glad that Roger did it, but I’ve always thought that if dad hadn’t gotten injured again that he would’ve probably done it, too,” David Mantle said. “He was just happy that Roger did it. He was really happy that one of them did it.”

Battling Mantle couldn’t compare with challenging Ruth. A living legend isn’t as intimidating as an immortal.

The Great Bambino’s stature had only grown in the 13 years since his death. Twisted fans protective of Ruth’s record responded with hate mail and death threats to a family-oriented, mild-mannered Midwesterner whose sole crime was success.

“It’s not like dad didn’t get it,” Maris Jr. said. “He wasn’t Babe Ruth. He wasn’t Mickey Mantle. He was a guy from the [Kansas City] A’s who knew who the hell he was. All of a sudden, he beats Mick and he’s starting to take down Babe, and he was not the immortal that they wanted.”

Some of baseball’s greats — most memorably, Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby — also wanted a different representative for the illustrious mark.

“It would be a shame if Ruth’s record got broken by a .270 hitter,” Hornsby said then. “He has no right to break Babe Ruth’s record.”

Ruth’s family — most notably, his wife, Claire — felt the same. They still speak on his behalf.

“It meant so much to him,” said Ruth’s granddaughter, Linda Tosetti. “He was the inventor of the home run.”

Still, Maris would have welcomed Ruth’s shadow if it hid him from the press.

“He hated being the centre of attention,” said Steve Jacobson, who was in his second season as Newsday’s Yankees beat writer. “He didn’t really fit in. He came from Nowheresville. He was cranky, and with the pressure of the home runs, he was uncomfortable. It wasn’t his nature. It wasn’t Mantle’s either, at the beginning, but at that point in his career he was pretty comfortable with it. Mantle had a sense of humour. He would tease himself. In a lot of ways, Maris was a pain in the ass.”

Maris’ tolerance for answering different versions of the same questions waned as his home run total increased, as media scrums grew larger, as national and non-baseball reporters sought more information about his life outside the batter’s box.

One reporter angered him by asking, “Do you play around when you’re on the road?” When Maris went home to meet his new son, Randy — born on August 21, one day before his father hit his 50th home run — a Kansas City newspaper printed their home address, attracting fans seeking autographs.

“It was a relief when the ballgame started and I could take my swing,” Maris said.

The chase didn’t change his temperament; Casey Stengel once said, “You ask Maris a question and he stares at you for a week before he answers”. The fuse just got shorter.

“I was born surly, and I’m going to stay that way,” Maris said at the end of the ’61 season. “Everything in life is tough. Even the Yankee clubhouse attendants think I’m tough to live with. I guess they’re right. I’m miffed most of the time, regardless of how I’m doing.”

The physical toll of altering history eventually caught up with the emotional stress. In September, Maris learned he was missing patches of hair in the back of his head.

“He was his own worst enemy as far as not enjoying what he was doing,” Sheldon said. “He put too much pressure on himself and he went through a lot of tough days, but he played with a lot of courage.”

On Labor Day, Maris had 53 home runs. October couldn’t come soon enough.

“I wish the damned season were over right now,” he said then. “The closer I get, the more I want it, but the more I wish the year was over.”

***

Ruth had so many supporters. Only one truly mattered: commissioner Ford Frick.

Frick, a former sportswriter, was the ghostwriter of Ruth’s autobiography and cherished their friendship — their wives played bridge together — visiting The Babe on his deathbed.

After two American League teams were added (Washington Senators, Los Angeles Angels) and eight games tacked onto the schedule in 1961 — the first change in the length of the season since the inception of the AL in 1901 — Frick waited until July 17 to announce that if Ruth’s record were broken in more than 154 games, it would necessitate a separate listing. The infamous asterisk was never official, erroneously earning infamy after a question to Frick from sportswriter Dick Young.

“Frick was always good with the decision,” said David Bohmer, a Frick historian. “There was never any regret. Frick made some comment earlier in the season that he didn’t worry about Ruth’s record being threatened. Then, of course, when the reality hit him, he changed his mind. He probably did overstep his authority because it probably should’ve gone through the rules committee to make the decision. He took liberty with what power he had to make the ruling and protect The Babe.”

Frick’s decree wasn’t controversial when it was announced.

Stan Musial said it was “a good rule.” Warren Spahn said, “In order for it to count, they should do it in 154 games,” Mantle said, “I think it’s right … If I should break it in the 155th game, I wouldn’t want the record.” Whitey Ford said, “It’s got to be done within 154 or it won’t mean anything.”

A pair of Sporting News polls of players and writers showed at least two-thirds of both groups in favour of Frick’s ruling. Maris was in the minority, criticising the commissioner for the mid-season decision, which made Game 154 (September 20) in Ruth’s hometown (Baltimore) the most nerve-racking of Maris’ career. He entered with 58 home runs.

“He was getting real nervous and smoking a lot and wanting to get away from the press,” Sheldon said. “I saw him walk out and go under the stands at the stadium, and I just followed him out there. As he was smoking, I just talked to him about what was going on and the pressure of everything.”

Maris told Houk he didn’t want to play. Houk told Maris to start the game and the manager would pull him, if Maris requested it. Maris crushed a first-inning pitch to right field. The heavy winds from nearby Hurricane Esther denied him his 59th home run. That would come in the third inning.

“He hit several balls that I thought were gonna be home runs,” Sheldon said. “The wind held ’em up.”

Maris’ final chance to tie Ruth in 154 games came against knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm, who was brought in for the ninth inning and induced a weak ground ball from Maris on a check-swing. The Yankees won 4-2, clinching the American League pennant. One New York newspaper ran a headline that read, “Maris Fails”. The post-game celebration shared a different sentiment.

“We were on the bus, and all of a sudden Mantle and Maris took out bags of crabs they had gotten and started passing them out,” Sheldon said. “It was the first time I ever had a crab.”

Maris remained stuck on 59 with five games remaining. All he endured could easily have ended with a forgotten second-place finish.

“With the pitches I’m getting, Daddy-O, I’ll never do it,” said Maris, entering the final homestand. “I just can’t swing the bat anymore. It’s amazing how the thing can get to feeling like lead.”

***

Pat Maris received updates on her husband’s exploits from phone calls, from newspapers, from private viewings of his highlights at the local television station.

The Marises had tried to move to New York earlier in the season. Briefly, the family of five crammed into a one-bedroom dwelling near Yankee Stadium, but ultimately, Maris and his pregnant wife decided they couldn’t find a place with enough space, a home worth leaving the one they loved in Kansas City.

The season’s final days brought Pat back to The Bronx. With Merlyn sitting beside Pat near the Yankees home dugout, Maris tied the single-season record on September 26, moving an also-present Claire Ruth to tears. The shot came in his 684th plate appearance of the season. Ruth’s 60th home run came in his 687th plate appearance.

Finally, recognition would be received. The stadium, less than half-filled, erupted with a standing ovation and a “most unusual” request for a curtain call, Allen noted. Maris put one foot on the top step, waved and went back into the dugout.

“I didn’t know what to do,” Maris said afterward. “I’ve never been in the situation before. I was in a fog. I thought I might feel silly.”

When Maris reached his locker after the game, he opened a nearby cooler.

“First of all, I need a beer,” Maris said. “… It’s the greatest thing that ever happened to me. … Being close, I wanted it. Now I’ve got it. I’m kind of bewildered. I really couldn’t say how I feel except I feel good.”

Maris had limited at-bats left. Only four games remained. Less than two weeks earlier, he’d gone seven straight games without homering. Maris decided to sit out for the first time all season. As the Yankees battled the Orioles in The Bronx, Maris went shopping with his wife in Manhattan.

“Roger was an unusual person,” Richardson said. “He didn’t care about individual records. He’d just as soon sit out a game and not get the record. I hate to say it, but that’s the way he was. It didn’t mean that much to Roger. Even on that last day of the season, he said, ‘I’d just as soon sit out.’”

Mantle and Maris drew crowds all summer. Maris hit his 50th homer in front of a sold-out stadium in Los Angeles. Roughly 65,000 fans came to an important battle for the pennant against Detroit. But on October 1, only 23,154 came to Yankee Stadium for the regular-season finale against the Red Sox. So many tickets went unsold due to Maris’ lack of popularity and Frick’s diminishing of a new record being set in 162 games.

Left field was empty. Right field was packed. A California restaurant owner named Sam Gordon offered $5,000 to whoever caught the 61st home run. It came on a fourth-inning pitch from Tracy Stallard.

“I was in the bullpen and we tried to creep up to the fence to see where it was gonna go,” Sheldon said. “We were all excited he did it. We were hoping he’d hit in the bullpen so one of us could get it.”

Mantle watched from a hospital bed.

“I got goosebumps,” Mantle told the New York Times in 1986. “That was the greatest single feat I’ve ever seen in sports.”

Then came the famous curtain call. Teammates wouldn’t let Maris back in the dugout, pushing him backward. He had to embrace the moment. He had to experience joy, respect, appreciation.

“He’s not a Reggie Jackson to come out of the dugout, so we had to push him out just to tip his hat,” Richardson said. “I was one of the guys who said, ‘You need to get out there quick, just for a step’. He did it, but he didn’t want to.”

Sal Durante, a 19-year-old truck driver from Brooklyn, was at the game with his fiancee when he caught the shot into the right field grandstand. Durante was escorted away by security, wanting to present Maris with the ball. The new home run champ declined the offer, setting Durante up for a fully-paid honeymoon the next month.

“The boy is planning to get married and he can use the money, but he still wanted to give the ball back to me for nothing,” Maris said. “It shows there’s some good people left in the world after all.”

Maris left the park and went to a Roman Catholic mass. He left minutes later, when his presence was announced. He then visited Mantle at the hospital.

Maris entered the day at peace. No matter the outcome, the saga would end.

“No one knows how tired I am,” Maris said afterward. “I’m happy I got past 60, but I’m so tired. I’m just glad it’s over.”

Maris again edged Mantle in the MVP vote (202-198). The Yankees beat the Reds in the World Series in five games. Maris delivered a ninth-inning homer to win Game 3 and put the Yankees in front for good.

His treatment from fans only grew worse in five more seasons in New York. People who were disgusted that Maris passed Ruth would hate him even more for never approaching unprecedented heights again.

“Does he wish he broke the record? Of course. But then he got trashed the rest of his career and was never appreciated for what he did,” Maris Jr. said. “That’s what used to upset him. Anyone who wanted to talk to him only wanted to talk about his 61 home runs.

“It was great he broke the record, but even to this day, unless you know anything about baseball, people go, ‘Roger Maris was a one-year wonder’. That’s what people say and that pissed him off. He was a back-to-back MVP!”

***

Maris, a father of seven, was 51 when he died of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1985. Six years later, the home run record finally and solely belonged to him, following a ruling from commissioner Fay Vincent.

“That would’ve meant a lot to him to be recognised for what he did,” Maris Jr said. “He never really got recognised for what he did. The whole time he lived, he had to live under the fact that he did it because he had more games.”

Maris wasn’t around to see one of sport’s greatest feats beaten twice in 1998 (Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa), twice in 1999 (McGwire, Sosa) and twice in 2001 (Barry Bonds, Sosa). He wasn’t around to see his legacy elevated in the 21st century as a slugger who didn’t need performance-enhancing drugs — each player to top Maris has been kept out of Cooperstown because of ties to and/or admission of such use — who did it despite inhaling unfiltered Camel cigarettes.

The most storied record in sports is stained, likely to never be cleansed. Barring an extra 20 games being added to the MLB schedule and/or fences moving in by 80 feet and/or metal bats making it to the majors — what’s sacred in the age of seven-inning double-headers and extra-inning ghost runners? — 73 home runs shall never be topped in a single season.

Should the impossible ever occur, the player who tops Bonds would be treated like a loved one, cheered and supported in every at-bat. Somehow, someone broke baseball’s most cherished mark when the world just wanted him to disappear.

“As a ballplayer, I would be delighted to do it again,” Maris said years later. “As an individual, I doubt if I could possibly go through it again.”

- New York Post