Chris Anstey: My year as a Chicago Bull after the Michael Jordan empire crumbled

When the lights came on after The Last Dance, Chicago was a demolition site. CHRIS ANSTEY was right in the middle of it all as Michael Jordan briefly returned – but only to whoop a trash-talking kid.

As The Last Dance, the acclaimed documentary series based around the 1997-98 NBA season, faded to black, the on-screen caption read: ‘Following Chicago’s sixth championship in eight years, Phil Jackson was replaced. Michael Jordan went back into retirement. Scottie Pippen was traded. Dennis Rodman was released. Steve Kerr was traded. And the Bulls began to rebuild.’

The timing of the NBA lockout that delayed the 1998-99 season was almost prophetic. If there was no Chicago Bulls dynasty, there was no NBA. The Collective Bargaining Agreement dispute between players and owners ensured there were no NBA games played for eight months after Michael Jordan hit ‘The Shot’ – the final basket of his Bulls career to beat the Utah Jazz in Game 6 of the NBA Finals.

When the dispute ended and the NBA limped back into action in February 1999, only Toni Kukoc, Ron Harper, Bill Wennington, Randy Brown and Dickey Simpkins remained from the Bulls’ last championship roster. As Tim Floyd took over as coach from Phil Jackson, the Bulls struggled through a 13-37 season, good enough for third-worst in the NBA.

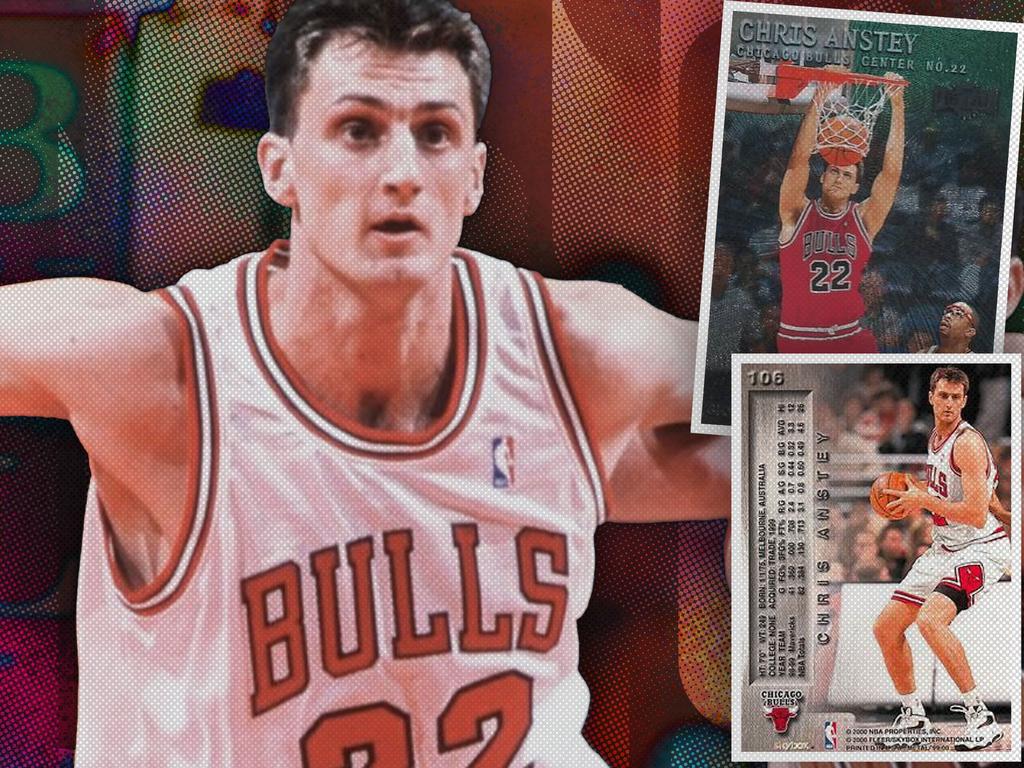

Following the train wreck that was the lockout season, the Dallas Mavericks traded me to Chicago. On draft day two years earlier, the Bulls were the only team that had guaranteed me they would use their only first round draft pick on me if I was available at the last pick of the round – their first selection – but I became a Maverick at pick 18. Regardless, after two seasons in Dallas, I was on the way to Chicago.

Other than trading away a second-round draft pick for another seven-foot Aussie following the path of Luc Longley, the most obvious benefit of the 13-win season for the Bulls was getting the first pick in the 1999 draft. The Bulls used the top pick to select Duke University standout Elton Brand, and they also drafted St John’s University forward Ron Artest at No. 16.

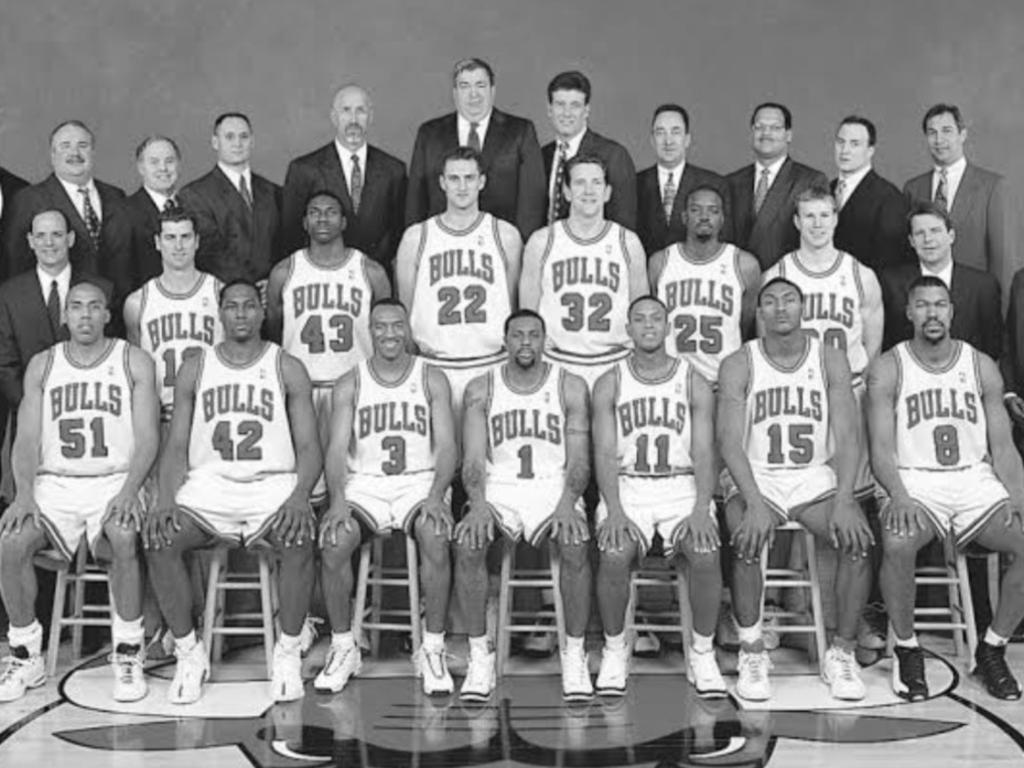

Perhaps realising that their young recruits needed some veteran guidance, and needing some extended goodwill from Bulls fans, the team also brought back championship winners BJ Armstrong and Will Perdue, along with highly respected veteran and Chicago native Hersey Hawkins. Our 1999-2000 roster appeared to have a mix of experience and excitement.

The Bulls trained at the Berto Center in Deerfield, 40 kilometres north of downtown Chicago. As hard as the previous season had been, there was no doubt that building still held an incredible aura. Six NBA Championship trophies greeted me as I walked in the door for the first time. The corresponding championship banners hung on the walls of the practice court. The Chicago Bulls logo represented greatness. I was handed my Chicago Bulls training gear. Crazy.

The thing was, despite all those recent titles, there was no pressure to win. Everyone knew we were going to be bad. Tim Floyd was still adjusting to the NBA after more than a decade of college coaching, and the fans were still basking in the afterglow of the greatest team of all-time. The fans were realistic. They knew how fortunate they had been.

‘I heard you been running your mouth. Let’s go’

In situations where people are busy trying to adjust and prove their individual ability to others, very little collaboration or growth occurs. Tim Floyd was still trying to prove he could coach professional players, former bench players were trying to prove they could play bigger roles, rookies were trying to prove they belonged, and – entering the last season of my rookie contract – I was trying to prove I deserved another NBA deal. As the losses piled up early, it became increasingly apparent that we were in it for ourselves, not each other.

One of the young players trying hardest to prove he belonged was second-year guard Corey Benjamin. On a team without established leaders, he was able to voice his opinion without being put back in place as quickly as he otherwise might have been.

We started the season 0-5 and Benjamin logged very few minutes. Not only was he already becoming vocal in his belief that he deserved more minutes, but he went as far to say he could beat anyone in the world one-on-one, including Michael Jordan.

Word got back to Jordan that a young kid on the team had been running his mouth.

As we finished our first session back from a road trip, in strolls Michael Jordan. Basketball in hand, he walked straight up to Benjamin, who was shooting on a side rim. ‘I heard you’ve been running your mouth,’ Jordan said. ‘You and me. Let’s go.’

An incredible athlete and an exceedingly confident human being, at that moment Corey Benjamin was the furthest thing from it. ‘Um, shoot for it?’ Benjamin stuttered to Jordan.

‘Look around you,’ Jordan replied. ‘What do you see? See all those championship banners. They’re mine. It’s my ball.’ And it was.

Wearing long sweatpants and a cut off T-shirt, Michael Jordan proceeded to give Corey Benjamin a clinic as our team and staff watched on. The players who had been around for years chuckled. They had seen this before. Those of us who were new just watched in fascination. Even after being retired for more than a year, Jordan could still score in so many ways, and his trash talking was as sharp as his game.

‘You reach, I teach,’ Jordan said as he shot a turnaround jumpshot. ‘Come on down here with me,’ he taunted as he manoeuvred Benjamin to the low block before spinning and scoring on him. ‘Don’t call me out of retirement for that garbage again,’ came the parting verbal shot as Jordan completed his dismantling of the young, now less-confident Corey Benjamin.

Metta and his monster truck

Another young and talented player on our roster was Ron Artest (aka Metta World Peace, aka Metta Sandiford-Artest). The Bulls knew when they drafted him, and his teammates would quickly learn, that Ron marched to the beat of his own drum.

Having dealt with Dennis Rodman, the Bulls front office knew the blueprint to managing different – and difficult – personalities. Or so they thought.

From the start, Artest would push boundaries. He would be late to training sessions and games, was reckless at training and difficult to be around at times. He would be fined and reprimanded according to our team’s rules and guidelines.

Having lived in New York City his entire life, Artest had not had to drive. Early in his first season in Chicago, he got his driver’s licence and bought a monster truck. Everyone joked with him when it did not fit through the Berto Center driveway, forcing him to walk into practice from the street. It was a little less fun when he received a big team fine for missing the start of a game because his truck took two lanes on the freeway and was too big for some streets.

That said, I am still not sure anyone – especially among the Bulls management and coaching staff – took the time to understand Ron, to ask why he acted out. Phil Jackson had been a master at embracing and blending different personalities, whereas Tim Floyd had come straight from coaching Division 1 college basketball where one size fits all. There was no room for anyone to be different or be treated differently.

A house in decline – renovate or rebuild?

In the absence of continuity and consistency on the court, the scramble to selfishly pursue our own individual opportunities as the season rolled on was tempting, and while we were doing so our focus shifted away from the plight of others. It became an ‘accidentally’ selfish culture and there were few highlights in a 17-65 year, but there were lessons. Plenty of lessons.

The 1999-2000 Chicago Bulls were filled with fantastic players and staff, but even so my biggest lesson was understanding how disjointed a team can become when individuals are pulling in different directions, even if each person has good intent. It was also hard not to feel hurt being involved in the dramatic decline of a franchise that had been so successful.

The Michael Jordan era was amazing, but its shadow loomed long and large over the Bulls franchise for years after he cleared his locker for the final time. In fact, in the 22 seasons after Chicago won its sixth NBA title, the Bulls have advanced past the first round of the playoffs just four times. Only now, as the 2021-22 season reaches its midpoint, do Bulls fans again have genuine hope of a deep playoff run.

Through the nine seasons Phil Jackson coached, the Bulls won six championships, reached the eastern conference finals once and the conference semi-finals twice. Jordan and Scottie Pippen were the only players to feature in all six championships and all nine seasons.

I would argue the Bulls retooled and renovated for the duration of Phil Jackson’s tenure. Their three leaders – Jackson, Jordan and Pippen – stayed consistent and challenged others, all while evolving themselves. Jackson was one of the best coaches in history, but not only because he won. Jackson not only accepted, but embraced difference, and was able to maximise its potential. It set him apart from his peers and laid a foundation for sustained success.

While the Bulls rebuilt, former Bulls players continued to win in the immediate post-Jordan and Jackson seasons. In fact, four of the next five NBA Champions featured Bulls title winners – Steve Kerr, Will Perdue, Ron Harper, John Salley and Horace Grant – who had all been moved on.

When it comes to a house in decline, you either renovate or rebuild. When you renovate, you improve a few things, but keep the soul of the home. When you rebuild, you demolish the house, you knock everything down and start again with a new vision. People rarely demolish beautiful, sound homes.

In my year at the Chicago Bulls, I never felt I was a part of a rebuild. I felt like I was part of a team wading through a demolition site. The team itself felt as temporary as a site manager’s portable office on that site.

At best, I would describe my season as a Chicago Bull as transitional. Everyone was given an opportunity to stand out, me included. But those opportunities often came at the expense of others, not in alignment with them, and at the expense of the group. If players did not improve, they were replaced, not developed, victims of impatience. It was like being caught in a rip. The club was in a hurry to save itself, but the harder we fought, the worse we became.

I am proud that I pulled on a Chicago Bulls jersey for an NBA season. My No.22 jersey still hangs on a wall at home and offers a constant reminder that sometimes life gives you the test first and the lesson later. I learnt more from my Bulls season after it was done than I did during it. I wish I knew then what I know now.

As Joni Mitchell sang in Big Yellow Taxi,

Don’t it always seem to go,

That you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone,

They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.

1999-2000 Chicago Bulls

Chris Anstey

BJ Armstrong

Ron Artest

Corey Benjamin

Elton Brand

Randy Brown

Chris Carr

Kornel David

Hersey Hawkins

Fred Hoiberg

Lari Ketner

Toni Kukoc

Rusty LaRue

Matt Maloney

Will Perdue

Dickey Simpkins

Michael Ruffin

Dedric Willoughby