Mike Atherton: The four-week making and 30-year aftermath of Shane Warne’s ‘Ball of the Century’

As we approach the 30-year anniversary of the ‘Ball of the Century’, Mike Atherton takes us inside the England dressing room as Shane Warne shocked Mike Gatting and the world.

‘Twas the first Test of The Ashes series 1993

Australia had only managed 289 and we

Felt all was going to plan, that first innings at Old Trafford

Then Merv Hughes and his handlebar moustache dismissed poor Athers

I took the crease to great applause and focused on me dinner

I knew that I had little cause to fear their young leg spinner

He loosened up his shoulders and with no run up at all

He rolled his right arm over and he let go of the ball …’

Thirty years on (this coming Friday is the anniversary), Shane Warne’s “Ball of the Century” to Mike Gatting has not been forgotten: The Duckworth-Lewis Method wrote a song about it, excerpt above, called Jiggery Pokery; the clip of the ball has been viewed millions of times on various platforms; it is still referenced whenever a spin bowler produces a bit of magic; and is remembered more mournfully now, of course, 15 months on from Warne’s death.

Others who were tangentially involved have also died. Richie Benaud, himself a world-class leg spinner, who once bamboozled England at Old Trafford, called the moment with his customary economy and style. You can just picture Benaud in the mind’s eye raising a quizzical eyebrow as he says: “He’s done it.” There was no screaming or shouting, just a pause to let the moment sink in and then: “He’s started off with the most beautiful delivery. Gatting has absolutely no idea what has happened to it … he still doesn’t know.”

So has Terry Jenner, Warne’s coach, who had been speaking at a function at the Melbourne Cricket Ground the moment his pupil entered Ashes folklore. Jenner’s reaction, according to Gideon Haigh who recounted the anecdote in this year’s Wisden Almanack, was unprintable because the day before the two had connected over the phone and they had agreed that Warne should ease his way into the Ashes. Go carefully, you know, and settle in before looking to do something a little more ambitious.

The man who coined the phrase “Ball of the Century” was the former cricket correspondent of The Sunday Times, Robin Marlar, whose memorial service was held at Lord’s six weeks ago. Marlar had a day’s grace to file his report, but he felt the need to reflect on the moment, and his description has stood the test of time. Marlar was a spinner himself (he had taken 970 wickets bowling off spin for Sussex and Cambridge), and knew he had seen something special that needed recording for posterity in The Sunday Times archive, which is where it now sits.

“The Ball of the Century we can safely call it, was the very first from Shane Warne in a Test in England … Up he skipped, ripped his fingers across the seam and released The Ball. Those of us lucky enough to be behind the arm thought it was the flipper because, as it arced it began to swing towards the leg side, fading further as it hovered and fell. It dropped on the edge of the quick bowlers’ second footfall, at least a foot outside Gatting’s advancing left leg.

“Now, we thought, watch it go on down the leg side. If Gatting is quick he might swat it with a sweep. But this was no flipper, rather an inspired leg spinner, which, having dropped, bit and bounced steeply. It travelled past the outside of Gatting’s bat, past his back leg and just tickled the outside of the off stump. Utter perfection, sporting skill elevated to fine art.” Quite.

The most recounted anecdote from before that Old Trafford Test comes from Worcester, where, in the second innings following-on, Graeme Hick put a dent in the young spinner’s confidence (23-6-122-1) when he smashed 187 in the tourists’ traditional opening first-class fixture at England’s most picturesque county ground. It is well known that Allan Border, Australia’s captain, had instructed Warne not to show all his tricks against Hick and had kept Warne out of view in the ODI series that followed.

But Warne had made his mark on others who played against him in the run-up to the first Test which, as was habit then, was extensive. He played in four of the first-class warm-up matches against Worcestershire, Somerset, Surrey and Leicestershire, as well as one-day games against an England Amateur XI at Radlett, and the Duchess of Norfolk’s XI at Arundel. Before the World Test Championship final this year, Australia will practise behind closed doors at Beckenham and will have no county matches before or during the Ashes – how times change.

That was one of the glories of touring then, and an Ashes tour was a favourite of the Australia players because of the camaraderie that ensued, travelling around the country on the team bus, enjoying the variety that a four-month tour would offer. As Hughes told the young leg spinner on the flight over: “It’s a great tour: no flights; free beer from the sponsors; the county games are no sweat and the Tests have rest days. Best of all, England are crap.”

Hard to think now, but the greatest leg spinner that the game has seen, played his first match for Australia in England at Radlett, a club ground in Hertfordshire. There is still a framed memento of the day in the club’s pavilion. Steve Dean, the father of Charlie Dean, the England women’s cricketer, opened the batting for the England Amateur XI that day but was out just before Warne came on to bowl.

Instead, it was left to Mel Hussain, brother of Nasser, to hit Warne for the first six of the tour, a towering shot in the first over after tea that took some tiles off the roof of the Radlett pavilion. Hussain remembers facing one over from Warne before tea – which he didn’t lay a bat on – and then the six. Hussain recalls that Micky Stewart was the manager of the Amateur XI and that he, Hussain, was tasked with seeing how Warne reacted under pressure. Clearly, the swashbuckling genes in the Hussain family were distributed unevenly.

Then to Worcester, and a pounding from Hick, and then to Taunton for a second first-class game against Somerset, which Australia won by 35 runs. Nick Folland, who came late to a short spell in professional cricket because of a teaching career, played in that match for Somerset and was dismissed twice by Warne. Now living in Perth, Australia, he tells me he remembers a spinner who “bowled it quickly, spun it hard and was very hard work to face”. In the second innings, chasing 320, Folland (32) and Andy Hayhurst (89) were going quite well and Folland remembers hitting Warne over long on and sweeping him for boundaries.

“He was bowling around the wicket and I remember Andy’s wicket clearly because as he released it, Warne shouted, ‘That’s done him!’ and, sure enough, Andy was bowled around his legs.

“But I queried it with the umpire, questioning whether a bowler should be shouting while the ball was in mid-air. Andy had turned to walk back to the pavilion but I told him to wait. Anyway, the umpires conferred and gave him out, after which I got a fair bit of stick from Warne. Then he got me stumped brilliantly by Tim Zoehrer to one that spun a long way.

“They were great to play against. I remember them being very aggressive in the field, but after the game they all came in the changing room for a drink.”

It was only Mark Butcher’s third first-class game when he came up against Warne, in the spinner’s next first-class game, on May 25, 1993, so it is perhaps no surprise that he remembers the match clearly. “It was a low-key game, on a green, damp pitch and very cold,” says Butcher, who, like Folland, was dismissed in both innings by Warne, leg-before and stumped.

He recalls the second dismissal, stumped, vividly. “The ball nearly pitched off the strip and then spun over my right shoulder as I lunged at it, brilliantly taken by Zoehrer [Zoehrer, also a leg spinner, was Ian Healy’s understudy] behind the stumps. I guess he was strong then, was Warne, as this was before any injuries and I remember hearing the ball on its way down, humming. Fizzing, almost.

“After I got out I remember thinking ‘What the hell was that?’ It spun more than anything I’d seen before. So that was all before the Gatting ball, but he made a very strong impression on me. I probably didn’t face him again until the 1997 Ashes.”

So although Warne had only taken one wicket against Worcestershire, his form had been strong in the remaining first-class matches before the Old Trafford Test: five wickets against Somerset, seven against Surrey, and six against Leicestershire. Old Trafford was to be his 12th Test. He had taken 31 Test wickets at an average of 30 by this stage, but had shown glimpses of what was to come, with seven for 52 against West Indies at Melbourne, and 17 wickets in the preceding series against New Zealand. He was improving rapidly.

Alan Lee, the then cricket correspondent of The Times, wrote after the Somerset match: “Shane Warne, the 23-year-old who has already won three Tests, commands respect and he can now add Somerset to the list of teams bemused, bothered and bewildered by his varieties."

Reflecting on Warne’s 100th first-class wicket against Leicestershire in the final match before the first Test, Michael Henderson, Lee’s No 2, wrote in The Times: “It will be a lengthy list by the end of the summer.” So it was.

The weather was atrocious in the build-up to the Manchester Test, my 24th for England. It was so wet that there was talk in the media that Australia might play only one spinner, and on a sticky pitch that spinner might be Tim May, not Warne. England played two finger spinners, Peter Such and Phil Tufnell.

There was no discussion of Warne before the match among the team. Nothing now is hidden from view in professional cricket but this was way before extensive analysis was a thing, a surprise factor that must have benefited Warne that match. I cannot remember seeing any video footage before the game and the expectation that May might play dampened any speculation about Warne. At the traditional pre-Test dinner – long since abandoned now – there was no chat about him.

The pitch was very damp at the start, the reason why Graham Gooch put Australia into bat, although as a generation of captains discovered, this was a perilous business with Warne in the opposition. Warne then got to work on the second day, in the afternoon session, just before tea. The clock showed 3.05pm – five minutes past midnight in Warne’s home town, Melbourne.

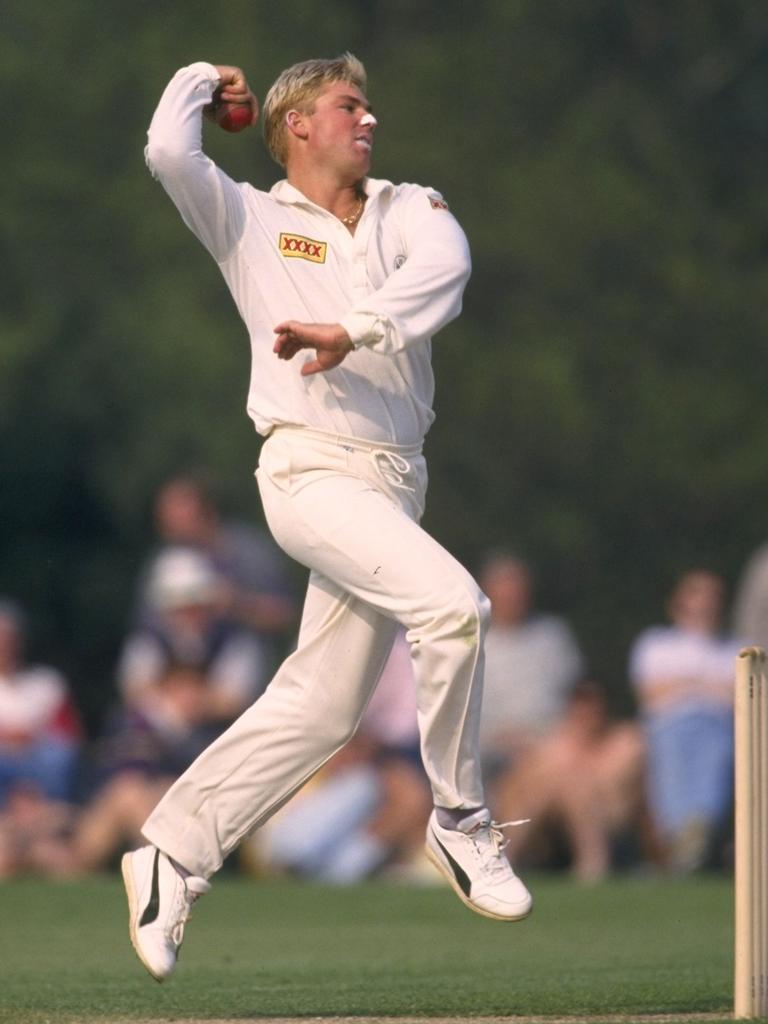

Looking at the YouTube footage now, you can see sawdust everywhere: a small pile behind the bowlers’ run-ups and spread around on the run-up footmarks, and Warne, before his first ball, jogs over towards a pile to retrieve the fast bowlers’ mark (in those days they were like small, round beermats whereas now the bowlers’ marks are painted on the outfield). Warne stood at the end of his run-up: peroxide blond hair, gold chain, a blob of sun cream on the end of his nose.

He bowled a practice ball to mid-on, paused a while to get the field right, and then, as Benaud intoned “first ball in Test cricket in England for Shane Warne”, he walked, then broke into a trot and released the ball from a low arm – maybe at 2 o’clock – which, along with the strength of his fingers and wrist, sent it humming towards Gatting, dipping and then swerving and then spinning beyond the batsman’s half-forward push.

More Coverage

Given the angles – to spin it past Gatting from outside leg stump and still hit the top of off stump – it was the perfect ball, the image made more so by Gatting turning to watch it hit his stumps, and then standing there, momentarily, in bemusement, his mouth making an astonished “O”. In the dressing room, we gathered around the television to watch the replay.

With this entrance Warne had entered Ashes folklore, although he was to take another 194 wickets in Ashes contests, more than anyone else by a distance. His legacy was assured, and it lives on through these memories, but more so because of the verve and zest with which he approached the game – and life – more generally. During the first Ashes series since his passing, he will be sorely missed.

Originally published as Mike Atherton: The four-week making and 30-year aftermath of Shane Warne’s ‘Ball of the Century’