In the week the Taliban advanced on Kabul, the grounds of Chamn-e-Huzuri still teemed with keen cricketers

On the day Australia‘s men were due to play against Afghanistan, Rahim Mushtaq reports from Kabul on the status of the game.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

As the Taliban advanced on Kabul, and Afghanistan was plunged into fear and uncertainty, the nation’s passion for cricket remained steadfast.

The fall of Ashraf Ghani’s administration in August left Afghanistan in tatters with a significant threat of chaos and disorder. The announcement of Ghani’s flight from the country, made by Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, the head of the National Reconciliation Council, left many here in Kabul and around the country scared and concerned for Afghanistan and our families. In the absence of the security apparatus, the major worry was that public and private property could fall prey to looters.

Against this backdrop of insecurity and instability, Taj Maluk Alam, the former coach and long-serving official at the Afghanistan Cricket Board, posted a photo to social media of him guarding the headquarters of the Afghanistan Cricket Board. “Keep it up brave man,” Natiqullah Khaskar replied. “Don’t allow looting; we want sport in all sorts of situations.”

Days later, as the Taliban consolidated power, the world watched on as thousands of people headed to Kabul International Airport in a desperate bid to leave the country on evacuation flights operated by international forces. Millions more chose to stay indoors.

But there was at least one familiar scene. In the middle of the deserted city, Chamn-e-Huzuri, the beating heart of Afghan cricket, remained a hive of activity. Shouts of “catch it!” … “how’s that!” … “good shot!” were a welcome sound amid the uncertainty enveloping the country.

Chamn-e-Huzuri is a vast field just a few miles from the Presidential Palace and was once dominated by football. That was until Taj and his team stuck their wickets in a corner and started the momentum of Afghan cricket about two decades ago.

Since then, the ground – now dusty due to its heavy usage by keen cricketers – hosts a large number of local players throughout the day, all week long. People young and old, wearing traditional clothes instead of whites, play cricket until the sun goes down with passion and enthusiasm, following all the rules of the game except for leg-byes and byes and no Leg Before Wicket.

That continued during the Taliban’s re-entry into Kabul.

It continues now.

From refugee camps to the world

The modern history of Afghanistan cricket can be traced back to the refugee camps in Pakistan in the 1980s, a period defined by the Russian occupation and fierce resistance by Afghans through guerrilla warfare.

Those camps, impoverished and comprised of basic mud house structures around Peshawar, were the breeding ground for the pioneers of Afghan national cricket including Taj Maluk, Raees Ahmadzai, Dawlat Ahmadzai, Karim Sadiq, Hasti Gul Abid, Nawroz Mangal and many others.

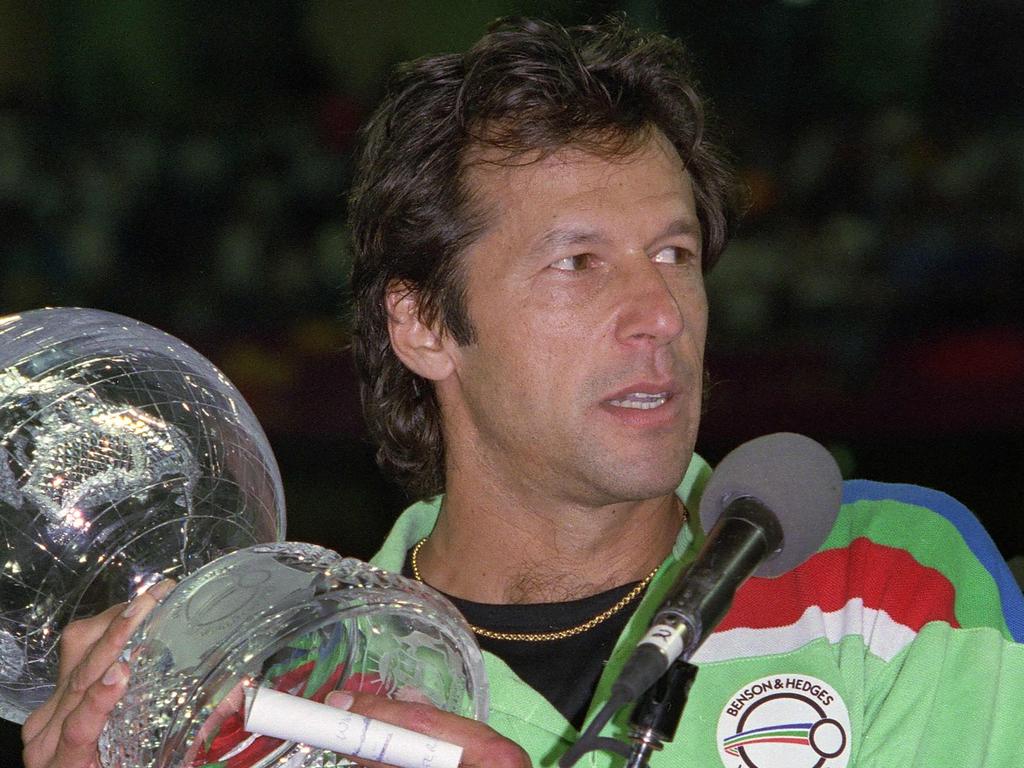

Following the departure of the Russians from Afghanistan and the subsequent collapse of the Russian-backed government, those figures, and many more, returned home with a burning passion for cricket. Not long after, Imran Khan lifted the World Cup in Melbourne – a source of inspiration for a generation of Afghanistan’s would-be stars.

By the late 1990s, a number of Afghan players took the game to the professional level, however, it was not until the US invasion in the autumn of 2001 that a formal institution for the game was established in the country.

It didn’t come easily.

“Even the national Olympic committee was not prepared to grant us membership,” recalled Raees Ahmadzai, the former captain and current national under 19s coach. “It was a time that we, as youth of the family, should be supporting our families. Instead we were burdening our struggling families for financial assistance.”

The zeal and dedication of Ahmadzai and his teammates, those who had graduated from tennis-ball to hard-ball cricket, were a driving force behind the Afghanistan Cricket Federation being awarded affiliate membership of the ICC in 2001.

Still, a lack of facilities continued to challenge those that dreamt of competing against the best in the world. Ahmadzai remembers the time he met Hamid Karzai, the president of Afghanistan at the time, and asked him to build a proper cricket ground.

“Karzai told me, ‘There are a lot of free spaces in the country, choose a place of liking and play’,” Ahmadzai recalled.

But as the team’s success grew, so did political support for the game. Players like Hameed Hassan, Mohammad Nabi, Dawlat Ahmadzai and many others, coached by Taj Maluk Alam, grew to be loved by the public. Their efforts helped rebuild national identity after generations of war and presented a positive face of Afghanistan to the world.

By this stage, cricket was enmeshing itself into Afghanistan’s popular culture. Local musicians recorded songs about the heroes of the game and the glory they brought to the nation. The first of those was Latif Nangarhari, an Afghan singer, who released a Pashto song that translated to, “I will win the game of cricket, and bring the World Cup home”. The song ignited the passion of people in large stadiums and, soon enough, singing a cricket song had become a source of fame, a route that even established singers chose to take.

The ACB assigned a renowned Afghan linguist, Mujawer Ziar, to develop a bespoke cricket vocabulary. Terms such as shpageeza for a six and saluriza for a boundary became popular – chanted even by late Dean Jones during his commentary stint at the Shpageeza League, Afghanistan’s domestic T20 competition. A number of cricket books were also published by Afghan writers, including Emal Pesraly’s History of Afghan Cricket and Jaffar Haand’s Cricket’s Three Centuries Long History, both in Pashto.

The introduction of social media around 2009-10 took the game to another level in terms of public engagement. Every ACB decision, every achievement, every failure immediately became a point of national discussion. It was also around this time that women’s cricket began to enter the public discussion in Afghanistan.

The news on June 22, 2017 that Afghanistan had been granted full member status by the ICC was greeted with an outpouring of public jubilation. Indeed, I remember shedding tears of happiness when being interviewed about the decision at the time by Matiullah Abid, a VOA journalist known as “Cricket Lala”, or elder brother in cricket.

Since then, cricket has continued to win over all segments of the Afghan society. Once considered the game of the Pashtun ethnic group, cricket is now owned by all parts of the country.

And then there is Rashid Khan, the undisputed idol for a generation of young Afghans. Kids across the country try to emulate his bowling action and dream of attaining his status. He is admired around the country, and particularly in his home of Jalalabad, which continues to produce many fine cricketers.

Because of the popularity of players like Rashid and Nabi, Afghans follow closely the major T20 domestic leagues around the world. Barber shops around Kabul almost always have cricket on TV screens to keep waiting customers engaged, while Afghanistan’s international and Shpageeza league matches are commentated on the radio. Meanwhile, Radio Television Afghanistan, Afghanistan’s state owned media, have launched a dedicated sports channel, while leading TV networks such as Tolo and Shamshad have weekly sports programs with cricket as their main content.

The story of Afghanistan is filled with stories of struggle and tragedy but cricket, one can confidently say, is one facet of the national identity that is defined by dedication, passion and love of the game.

An example of the national willpower.

Cricket, politics and the Taliban

As the Taliban began taking over offices in Kabul and across the country, Abdullah Mazari, the former international player and staunch supporter of the Taliban, appeared on social media with an armed group of Taliban fighters at the ACB’s headquarters.

While other businesses and industries exchanged hands with little public comment, cricket fans rose up to immediately rebuke Mazari on social media. The ACB, they reasoned, was an independent and non-political institution which should not appear to be part of the political wrangling in the country.

Their voices were heard and the former chairman of the ACB, Azizullah Fazli, was appointed as acting chairman of the ACB to avoid disorder. This was one of the first public appointments after the Taliban’s takeover, confirmation that cricket remained important to the public and the people in power.

While people of Afghanistan attempted to make sense of the abrupt political changes in the country, cricket marched on. The senior Taliban officials started meeting the male players at their residences to provide them with confidence about their own safety and security, mindful of their status as darlings of the nation.

In mid-October, the List A tournament, Ghazi Amanullah Khan Cup, was launched in southern Kandahar province. The draft was also conducted for the domestic T20 Shpageeza League and franchises were sold to the bidders within two weeks of the Taliban consolidating political power. The tournament, however, did not launch as planned due to bank closures and the unavailability of cash. Similarly, a men’s international series due to be played against Pakistan in Sri Lanka as part of the World Cup qualifier league did not take place due to the lack of availability of flights, although the national under 19s men’s team did visit Bangladesh for ODIs and a Test, the latter of which it won by three wickets in September.

Meanwhile, the struggle for the coveted leadership of the ACB under the Taliban regime intensified.

The former leadership, under chief executive Hamid Shinwari, worked hard to ensure organisational standards were respected and a continuity of ACB operations took place. With the men’s T20 World Cup fast approaching, efforts to uphold the plans drafted months earlier were undertaken. The tussle for power and influence, however, saw the newly appointed acting chairman, Fazli, gain the upper hand. The former administration was slowly, but surely, sidelined, and gradually eliminated from the management at the ACB.

Fazli had previously been ousted in the aftermath of the 2019 World Cup debacle, in which Afghanistan lost all nine matches. Still, he was desperate to take the seat permanently again and set about garnering support from all quarters, most importantly the players.

The effort saw many of out-of-favour players such as Hameed Hassan and Shahpoor Zadran gain selection in the preliminary men’s T20 World Cup squad at the expense of emerging players. The former captain, Asghar Afghan, was also swiftly drafted into the national camp and photographed meeting with Taliban officials.

The approach of the new ACB management prompted unease among fans and the ACB executive staff members. Even the T20 captain and Afghanistan’s cricket icon, Rashid Khan, chose to step down from the captaincy in dissent to the preliminary team selection.

But despite concerns over new leadership and management, Afghans’ love for cricket did not diminish, according to Bakhtiar Sahel, the former regional director of cricket at the ACB and sports journalist.

In Sahel’s view, the Covid-19 disruptions and, now, the change of regime has the nation starving for cricket. The men’s T20 World Cup was enthusiastically supported and Radio Television Afghanistan, as well as a number of regional stations, covered the matches with comprehensive pre- and post-match analysis from local experts.

“The match hours brought life to a standstill in some of the cricket hubs such as Nangarhar, Khost, Logar, Paktia, Kandahar, Helmand and other provinces,” Sahel said. “Youth groups planned in advance get-togethers for the high intensity games such as fixtures with India and Pakistan.

“An Afghanistan win will be celebrated with treats to friends and family members.”

Women’s cricket and the Hobart Test

The regime change in Afghanistan prompted fears of restrictions on women’s rights, freedom and mobility. That extended to women’s cricket in Afghanistan, with reports of a potential ban attracting strong reaction from the international community.

Official statements on the status of women’s cricket have been rare, with an Azizullah Fazli media interview in October one of the rare exceptions.

“We have spoken to the top Taliban government officials and their stance is that there is officially no ban on women’s sport, especially women’s cricket,” he said.

“They have no problem with women taking part in sport. We’ve not been asked to stop women from playing cricket. We’ve had a women’s team for 18 years, although it wasn’t a major team, we’re not on that level yet.

“But what we need to keep in mind is our religion and culture. If women adhere to that [attire] there is no problem in them taking part in sporting activities. Islam doesn’t allow women to wear shorts like the other teams do while playing football especially. That’s something we need to keep in mind.

“A Taliban official also recently said sport and politics will be kept separate and those who understand the game and are technically well-versed will be appointed into relevant positions. The government has told us it will support us in any way needed.”

Cricket Australia nonetheless took a swift and strong position following a media interview with Ahmadullah Wasiq, the deputy head of the Taliban’s cultural commission, on Australia’s SBS News.

“I don't think women will be allowed to play cricket because it is not necessary that women should play cricket,” Wasiq told SBS. “In cricket, they might face a situation where their face and body will not be covered. Islam does not allow women to be seen like this.”

CA promptly issued a statement saying the men’s Test between Australia and Afghanistan in Hobart would be postponed if the ACB did not support an international women’s program.

“If recent media reports that women’s cricket will not be supported in Afghanistan are substantiated, Cricket Australia would have no alternative but to not host Afghanistan for the proposed Test Match due to be played in Hobart,” the statement read.

“Driving the growth of women’s cricket globally is incredibly important to Cricket Australia. Our vision for cricket is that it is a sport for all and we support the game unequivocally for women at every level.“

The men’s Test match against Australia was eagerly anticipated in Afghanistan. According to Hakim Ahmadzai, an Afghan cricket analyst and commentator, the match would have marked the “beginning of a new era for Afghanistan cricket and represented much more than a one-off Test.” His words are echoed by US-based journalist and Afghanistan cricket author/historian, Jaffar Haand. In a recent interview he described as “cruel” any decision to boycott Afghanistan cricket.

“Cricket has nothing to do with the Taliban leadership,” he said. “It belongs to the people.”

In response to CA, Shinwari, shortly before he was replaced in office, spoke passionately about the importance of playing the match.

“Keep the door open for us,” he said. “Walk with us, do not isolate us”.

An Afghanistan national women’s team was formed in 2010, disbanded in 2014, and seemingly revived in 2020 when 25 players were awarded central contracts. There have been conflicting reports and statements of the team’s status since. Hikmat Hassan, the ACB’s former media manager and adviser on women’s cricket, said Afghan cultural restrictions offered challenges for the promotion of women’s cricket in Afghanistan.

The prevailing view within Afghanistan, however, is that the fate of the Australia-Afghanistan men’s Test should not be tied to the fortunes of women’s cricket in the country. According to Hassan, “Cricket is not just a game for Afghanistan, it is a tool for peacebuilding.”

“It has been one of the very few reasons that has continuously brought all segments of Afghan society together,” he continued. “It remains a powerful source of inspiration for Afghan youth, and could continue to inspire the Afghan nation at a time that the nation is desperate for survival.”

The ICC, for its part, has expressed concern for the future of women’s cricket in Afghanistan, but have yet to take actions similar to those of CA.

“ … Despite the cultural and religious challenges in Afghanistan, steady progress had been made in this area since Afghanistan‘s admission as a full member in 2017,” the ICC said in a statement. “The ICC has been monitoring the changing situation in Afghanistan and is concerned to note recent media reports that women will no longer be allowed to play cricket.”

Afghanistan is at a crossroads. Uncertainty about the political landscape and economic stability is ever increasing. One of the few things that is assured is the love for cricket. Indeed, it is one of the only reasons for cheer, happiness and hope among the people of Afghanistan.

Cricket in Afghanistan must continue.

For the sake of a nation that is in need of support on all fronts.