‘Don’t bring a bum football team here’: The Storm’s unlikely 25-year conquest of Melbourne

The message from Jeff Kennett to John Ribot could not have been blunter when the Storm came to Melbourne. Yet the reply said it all about an NRL dynasty in the making, writes SHANNON GILL.

The message could not have been any more blunt to John Ribot.

“Don’t bring a bum football team here,” warned then Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett.

Ribot was in Melbourne to try to win support for a crazy idea; a rugby league team in an Australian football town.

The Premier said it would fail unless the team was good, the trademark Kennett arrogance in full effect. Ribot replied respectfully, but firmly.

“We’re not coming down here to lose, we’re coming here to win,” he said.

As Ribot prepares to fly to Melbourne to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Melbourne Storm across a weekend of festivities, he can be satisfied he made good on that political pact.

Gathering Storm

The mid-90s might have been Kennett’s pomp, but Ribot was flying high too. He’d been the driving force behind the Brisbane Broncos, the expansion team dominating the ARL.

It allowed him to walk into his first meetings with Rupert Murdoch and Ken Cowley, who were starting their rival Super League, with bargaining power.

“When you negotiate your in, it‘s the best time to negotiate your out,” he offers.

If Ribot was going to put himself in the middle of the war between the ARL and News Ltd, he wanted an exit plan. And that exit plan involved a flight south, some winter clothing and a Melways.

A Melbourne team had been on the ARL’s agenda previously but nobody thought it could work. It was an AFL city they said.

“The ARL looked at it and said it couldn’t work,” Ribot says of the challenge he needed.

By May 1997, in what proved the only Super League season before peace was brokered, Ribot was spending most of his time in Melbourne conceiving a new club that would start the next year, regardless of the competition.

Bronco lieutenant Chris Johns was first to come on board, then football manager Michael Moore. In the boardroom Ken Cowley became chair and business luminaries such as Peter Lawrence, Ron McNeilly and Marcia Griffin steered the ship.

“They were all winners and great inspirations to our club, equally responsible for the success of the Storm as anything I did,” says Ribot.

No guarantees

The AFL talks today about generational investment into western Sydney and the Gold Coast.

It is a luxury Ribot did not have.

As the leagues unified for the 1998 season, spots in the now NRL were at a premium and some clubs would go. From 1997 to 2000, 12 clubs across the ARL and Super League either disappeared or merged.

In that climate it was hard to justify a club that had yet to play a game.

“We were ranked bottom on all the metrics when it came to be holding a place in the NRL,” Ribot explains.

So the equation became simple.

“It meant we had two years to get it right,” Ribot says.

“Unlike the AFL’s expansion into Queensland and NSW, there was not an endless chequebook.”

There were no guarantees from the NRL beyond two seasons, making it a “hard sell” when it came to the board, management, players and coaches.

“We couldn’t give them any more than a two-year contract.

“We didn‘t know where we were going to go. If it failed, it wasn’t going to linger on and get pathways and development up over a ten year period.”

In the Storm’s case, necessity would be the mother of invention. Winning was the only option.

“Clubs talk of building cultures,” Ribot says.

“But we had to bring it in from day one. We had to set it up to win.”

Creating a team and an identity

The first step in creating a winning team was to find a mentor. Ribot found a like mind in Chris Anderson, who coached the Bulldogs to a premiership in 1995.

“I met with him before the club was created and he was looking for a new challenge, he was just a winning coach,” Ribot says.

There would be no gradual development for an Anderson team, they would be combative from day one.

“He brought to the table an attitude towards coaching that was very aggressive, getting in the face of the opposition.

“In a short time, people understood that if you came to Olympic Park you were in for a football game.”

Once a greyhound and athletics track, the club’s first home had seen better days but was nestled in Melbourne’s sporting heart. Anderson and the Storm turned its imperfections into advantages.

“It was a skinny field because it wasn’t the proper size. For the occasion it was perfect for us, there was nowhere to hide and we built on it.

“The opposition didn’t like coming down here, within 12 months it was called ‘the graveyard’.”

Getting a coach was one thing, getting a team of competitive players was another.

“The hardest thing about getting the players down here was getting them on the plane,” Ribot says.

“Conceptually they thought, ‘The weather, it rains three times a day, why would I want to do this, I’ve got to travel every week’.

“But once they got down there and understood what the place was about and saw the MCG and the AFL, they thought, ‘Wow, how exciting could this be, to be involved in a city and club like this’.”

The targets were not necessarily the highest profile or biggest stars, but improving players hungry for success and opportunity.

Brett Kimmorley, Tawera Nikau, Marcus Bai, Robbie Ross, Robbie Kearns, Richard Swain, Dallas Johnson, Matt Geyer. All took the risk of two-year deals to create a name for themselves and the new club.

“They were just senior players on the up and they built great careers.”

They flourished with a devastating effect that nobody saw coming.

Pitch to the masses

Most of the players recruited were unknown to sports fans down south. However, the Storm made an important pitch for a player who could cut through the Melbourne market.

“We’d go out there and say, ‘The Brick with Eyes’ is playing,” Ribot remembers.

“People in Melbourne would say, ’Shit, we’ve got to go see this bloke’.”

That bloke was Glenn Lazarus. The man mountain had been in Ribot’s Broncos teams, but appeared to be done as a player when the Storm came calling.

A gruesome broken ankle had Lazarus, doctors and NRL clubs believing his career was over.

“We went to him and said, ‘Hey Lazzo we need some real leadership here and we’ll give you the best doctors and best physio to see if we can get you playing’,” Ribot recalls.

“Two or three times he thought this was getting too hard and there was too much pain … but he persisted and he was a champion for us. We put all our marketing campaign behind him.”

It was a marketing campaign that was rooted in pragmatism. The Storm did not expect to take on the AFL, instead they tried to complement it.

“We weren’t there to become your new football club, we weren’t there to take over from the AFL, we were there to become your second love.”

‘Everyone’s second favourite team’ became the evangelical cry that Ribot’s team literally took to the streets with.

“We did silly things like went to every Apex and Rotary club within a 100km radius, to tell them what the Storm stand for.”

And it worked.

More than 20,000 Melburnians turned up for their first home game at Olympic Park to see a defeat of North Sydney. Soon it wasn‘t just Lazarus they were talking about.

The electrifying runs of Papua New Guinean winger Bai crossed over to fans and novices alike in Melbourne.

On his way to the Dally M Winger of the year title, he inspired the corner of Olympic Park to be christened the ‘Marcus Bai Stand’ by a swag of new league fans.

“It was always the most heavily populated place in the stadium,” Ribot laughs.

Victory

The Storm exceeded expectations to make it all the way to a preliminary final in their first season.

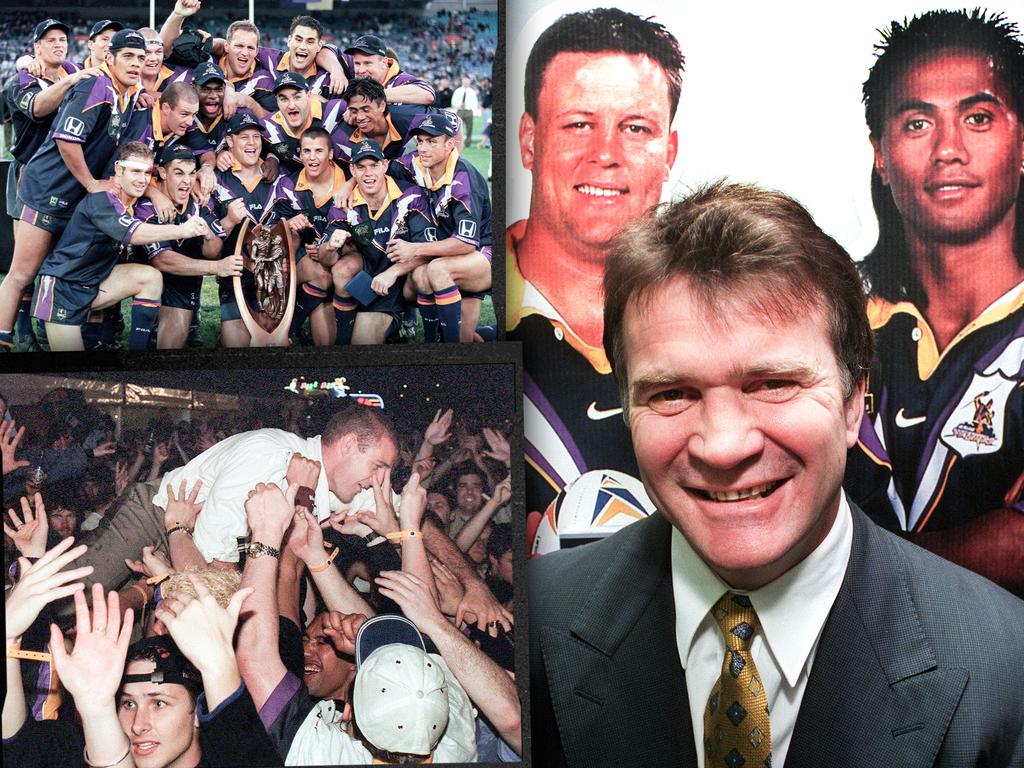

But just to ensure survival beyond that two-year deadline they did the unthinkable the next season; won the 1999 NRL premiership.

“I think the league were in shock,” Ribot says.

“A lot of people thought we were not going to survive. We were ranked worst in the competition.”

Ribot says the political machinations of a Super League created club in Melbourne meant many league loyalists wanted to see the Storm fail.

“From a political point of view, as silly as it sounds, for us to fail might have been an acceptable outcome for a reunified competition.”

“But that wasn’t in our plans.”

Some might say it still rankles many north of the Murray, stinging deeper with every bit of Storm success over the past 25 years.

Whatever the case, when Lazarus led his team off the tarmac at Melbourne Airport with the NRL premiership trophy in front of a sea of purple and blue, the future of the Storm was safe.

Off the field they were just as canny. During the 1999 NRL grand final, Victoria was in the middle of political chaos and a momentarily hung parliament after the state election. Ribot deftly hosted Victoria’s ‘two premiers’, Kennett and Steve Bracks, at the game … seated apart of course.

The relationship that started at the grand final between the Storm, Bracks and his chief of staff (now treasurer Tim Pallas) remains strong to this day.

It helped make the case for the building of AAMI Park, which further secured the Storm’s off-field future.

Legacy

The legacy has continued through the successful reign of Craig Bellamy and a string of iconic players, headlined by Cam Smith, Billy Slater and Cooper Cronk. They’ve survived the salary cap scandal to win more premierships and be the benchmark for excellence in Australian sport.

They are unquestionably the greatest expansion success story in Australian sport, perhaps even the world.

“What the board put in place and what the coaches put in place, and what Craig’s done since; the club is in such a good place 25 years later,” Ribot says.

“We realised that we were just caretakers, so it was just so important to get a winning culture right with good people.”

Ribot will catch up with Anderson, Bai and all the others who built the club from scratch on Friday night, when 70 Melbourne Old Boys form a guard of honour for the current side.

More Coverage

Then they’ll all attend the 25th anniversary dinner at Crown on Saturday, when Ribot will relive those wild days of the Storm’s birth.

“I still get goosebumps going to the football to watch them. I’m a silly old fart, but I just love what they stand for,” he reflects. “I like to think Melburnians relate to the Melbourne Storm as their team. A team they’re really proud of.”

You’d struggle to find anyone in Melbourne who disagrees.