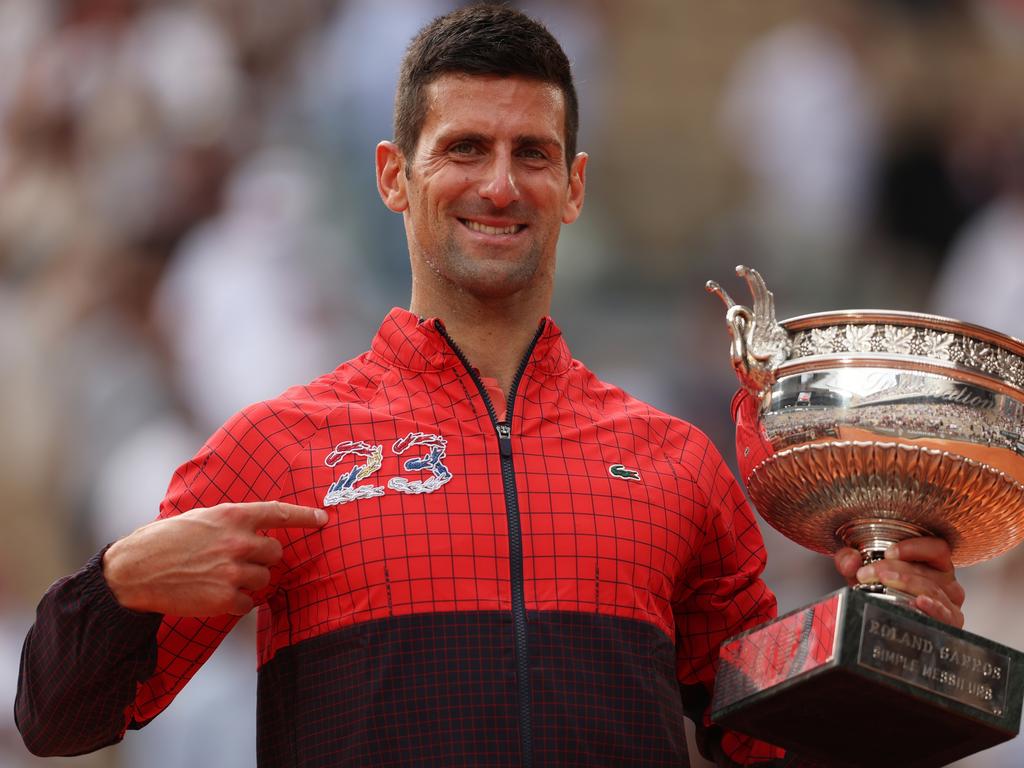

Jason Gay: Novak Djokovic stands alone after 23rd grand slam win, time to give him his due

Novak Djokovic was at his ruthless best in a crushing French Open final win against Casper Ruud. With his 23rd grand slam title won, his place atop men’s tennis is undisputed, writes JASON GAY.

Here we are, my tennis friends.

Most observers of this manicured sport have long assumed this day would happen. It felt as inevitable as one of our subject’s many and stupendous come-from-behind victories.

Novak Djokovic stands alone.

He has 23 major tournament men’s singles titles, more than anyone ever, after Sunday’s 7-6(1) 6-3 7-5 triumph over Casper Ruud. It gives him one more than Rafael Nadal, who has 22, and didn’t play Roland Garros this year due to injury, so if you want to asterisk Djokovic’s 23, asterisk away.

Doesn’t matter. Djokovic is going to keep going.

Which is what he does, relentlessly. The 36-year-old champion from Serbia is in the legacy-padding portion of his unprecedented tennis career, a tournament here, a tournament there, maybe miss a few, maybe lose a few head-scratchers, only look up in the second week in June and…

Djokovic is halfway to a calendar Grand Slam. Again.

So we’ll have that deliciousness this summer. Djokovic has won the Australian Open and the French and he’ll be the clear favourite in July at Wimbledon, where he’s defending champion and a seven-time winner.

Wait: check that. Djokovic is technically the four-time defending champion at Wimbledon—he won in 2018, 2019, and then the event was cancelled in 2020 because of the pandemic, and then Djokovic picked right up and won again in 2021 and 2022.

So Nole will be going for his fifth straight on the grass, a mark only accomplished by Roger Federer (2003 to 2008), Bjorn Borg (1976 to 1980) and by (yes you guessed it) long pants William Renshaw, who won six from 1881 to 1886. (Those of us who were there will of course remember Renshaw beat his twin brother Ernest in three of those finals. Shout out to Ernest.)

In late summer Djokovic will play the U.S. Open, which has been a bit of a snake pit lately—he was kicked out of the tournament in 2020 after accidentally hitting an official with a tennis ball; in 2021, on the edge of a historic calendar Grand Slam, he got thumped in the final by Daniil Medvedev; last year, he wasn’t able to play because of the now-dropped federal policy on unvaccinated foreign travellers.

You don’t think Djokovic is going to be motivated to win in New York? Look at what happened in Melbourne this year. He showed up to a country that threw him in the Covid clink and sent him home, only to return a year later, put his head down and take his 10th tournament singles title. Then he smiled and told everyone in Australia how much he loved playing there. He turned all that acrimony into a snuggle-fest. Pretty remarkable.

If you eliminate his vaccination drama, we would probably be at 24 majors. Maybe 25. Let’s say 24.

In real life, we’re at 23, with a clear path to more. Nadal is recuperating from hip surgery and has announced that next season—if he’s cleared to play—is going to be his swan song from tennis. Federer is done, happy and retired, showing up at a Knicks playoff game and F1 pit row and trying to sell everyone a pair of his fancy sneakers.

Tennis’s next generation? Hahaha. Hold on. I need to stop laughing. Tennis’s next generation has yet to crack the code on Djokovic or the Big Three mystique. Yes, Medvedev took the U.S. Open in 2021, and Carlos Alcaraz won it in 2022, but the former has been erratic, and the latter hasn’t figured out how to ration his athleticism and keep his body from breaking down.

Let me put it this way: Would you bet against Djokovic facing an opponent not named Federer or Nadal?

Me neither. The Next Generation seems stuck as The Maybe/Maybe Not Generation.

Consider Sunday’s final at Roland Garros. Casper Ruud is a very good tennis player! He’s the World No. 4, a finalist at the 2022 U.S. Open, also finalist in Paris last year, one of the best clay court players on the planet. The 24-year-old from Norway jumped right out to an early 3-0 lead and seemed to have the first set under his thumb.

Until he didn’t. Until Djokovic Djokovic’d him, with that lethal patience, making Ruud hit shot after shot, until he wearied and crumpled. It was a familiar execution, again on the biggest stage: The overworked up-and-comer outfoxed by the old wizard.

There’s a beautiful ruthlessness to it. Did you see the oilman epic “There Will Be Blood?” Djokovic’s the Daniel Day Lewis character. He drank Ruud’s milkshake. He reached his straw across the court and … drank … it … all … up.

I am totally entertained by this version of Djokovic. He is, on many days, the less powerful specimen on the bill—a wild thing to say, considering how long he reigned as the sport’s supreme body, who slept in recovery eggs, treated gluten like cyanide, and continues to turn to magic recovery crystals and whatnot.

But 36 is 36, even for Nole. Don’t get me wrong, he can still slip and slide and bend like Gumby on the baseline, and his endurance in four and five setters remains unmatched. He keeps himself physically elite. But his true Jedi superpower now lives upstairs, in the mental aspect.

Djokovic wins now by out-thinking you, stripping away your advantages, or using your advantages against you—letting you hit your hardest shot and making you do it again and again. Remember how he neutralised a peak Nick Kyrgios at Wimbledon last summer? At the French, his persistence cramped Alcaraz into a sad puddle in the semi-finals and he frustrated the skilful Ruud into repeated mistakes on Sunday.

It’s master class stuff, a tennis Ali doing the rope-a-dope in orange Lacoste. If you play tennis, and you want to know how an older player can torment a younger player, watch this version of Djokovic. Just watch Sunday’s first set comeback versus Ruud.

The crowd is grudgingly starting to appreciate this, and it’s about time. Djokovic was the Big Three’s third wheel, a youthful disrupter of Rafa vs. Roger, all but permanently cast as the nemesis. He regularly broke the hearts of the Fed fans and Nadal fans—he retains a lifetime winning record over both of them—and hasn’t experienced the warm bath of affection that those two routinely got. He’s been hissed and booed, and he’s occasionally contributed to this reaction, with some boorish behaviour on the court.

Sometimes Djokovic will lean into the hostility, using it as fuel—he once told me that when he heard the crowd cheering for an opponent, he imagined them cheering his name instead. I suspect he’s tired of those psychological gymnastics. Djokovic is no heel, he genuinely wants to be loved. He knows he will never be the dreamboat idol like Roger or Rafa, but he deserves his due. He should get it.

What’s a realistic final tally of major men’s titles for Djokovic? Twenty-six? Twenty-eight? Are we going to be watching him approaching 40, closing in on No. 30? Football ironman Tom Brady was with Team Nole at the men’s final; he probably views Djokovic as a mid-career sprite.

And yes, you’ll note that I’ve steered away from the “GOAT” talk here; I think it’s tricky to get into the “greatest of all time” talk in a sport with profound technological and lifestyle advancement. Rod Laver and the Aussies played with wooden sticks and stuffed themselves into a van to travel to make money at exhibitions. Give them all modern rackets, state-of-the-art strings, and a private jet, and we will talk about who would have beaten whom. Give 19th century Bill Renshaw a pair of lightweight shorts! He may have won eight Wimbledons in a row, four over Ernest, still in long pants. Sorry Ernest.

None of that is Djokovic’s problem, of course, and he will get the stage to himself. Every tennis obsessive should want Nadal to return to full strength and give it another go in 2024, get to another French final and rule the clay at the Summer Olympics in Paris. I want Alcaraz to harness his energy and body and become a clear heir apparent. I have no idea what’s possible. I imagine Rafa and Carlos don’t, either.

For now, Novak Djokovic keeps playing tennis with purpose. He stands alone, adding more.